Designs on eLearning 2015

When you get “The best elearning conference I’ve attended in 15 years” as feedback you feel you must have done something right. Over the weekend I’ve been musing on why we received comments like this and overall I think it comes down to the maturity of the discourse. It felt like elearning had grown up and avoided the normal tussle between the four main areas I see ascribed to the label ‘elearning’:

- Replicating core institutional functions at scale.

This includes eSubmission, making available content and generally moving paper-based processes into the digital. - Techno-solutionism.

Plugging in technology to solve particular problems with the assumption that once the technology is working ‘correctly’ the problem will be eradicated. (Often part of the drive in the approach above) - Fetishising the new.

Leaping on the ‘next big thing’ and claiming it will ‘revolutionise’ something. (linked to number 2) - Focusing on pedagogy and people.

Exploring how the tech can support forms of teaching, learning and engagement.

At DeL there was a healthy emphasis on number 4 with a concurrent wariness of 1, 2 and 3. Almost all of the sessions I attended discussed the complexities that arise when people and tech mingle. There was also a healthy skepticism of the Digital Natives idea, with very few people starting with that principle as a basis to build from (either directly or tacitly). It was as if the discourse around elearning had grown-up and become less polarised. Perhaps this was also helped by the mix of elearning folk, teaching staff and students. The parallel sessions had an honesty to them in which the subtly and complexity of teaching was respected (No ‘how can we foist this week’s cool tech on staff or students’).

Rhetoric and reality

What also stood out for me was an interesting tension between some of the keynote “the digital has arrived” rhetoric and the reality of developing elearning projects within institutions. This spawned the hashtag #undertheradar as most of what we heard in parallel sessions included a comment along the lines of “We didn’t really tell anyone we were doing this” or “We kept this quiet until we were sure we had the design right”. I’m wondering now if this is a response to the techno-solutionism approach which is gaining ground as institutions seek to stabalise and consolidate processes via technology. The iterative approach in which projects take a number of cycles to find their way is, in my opinion, the only way to develop the ‘pedagogy and people’ side of things. And yet despite the fact that we hear noises from the top that digital is the way forward we are still nervous about revealing the leading edge of our work. I wonder how we can gain confidence and make it clear that there is no ‘plug-and-play’ where we are looking to support pedagogy?

Digital segregation

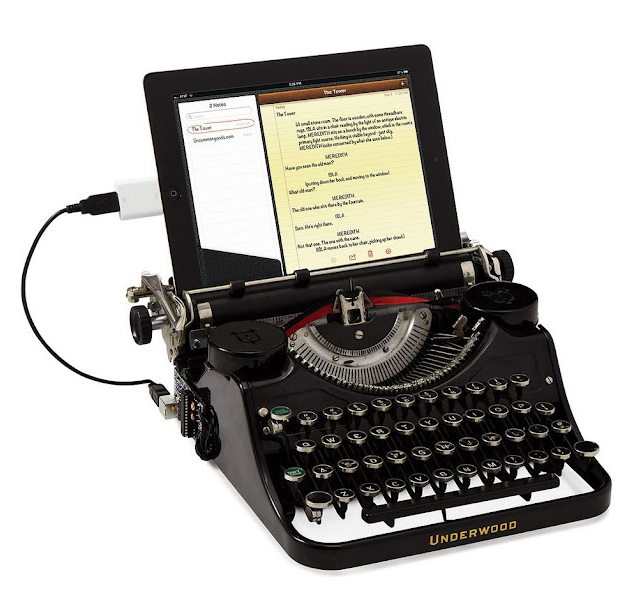

The second theme for me was closely linked to creative practice but stems from a more general challenge, namely that we still segregate the digital. This problem was mentioned in a few of the student keynotes which questioned the hiving off of expensive Apple Macs into pristine labs when the creative process often needed a multi-modal and messy environment. The truth is that the tech we buy as institutions to impress incoming students might not always be the tech they need to undertake their studies. This is a tricky one as a random set of slightly out of date, battered laptops isn’t going to look good but it might free students up and start breaking down disciplinary boundaries which are currently reinforced by the geography of our physical spaces and the fear of breaking expensive stuff. My hope is that the tech will become unchained one day in the same way books once were. For the time-being the march of technology and consumerism is too strong.

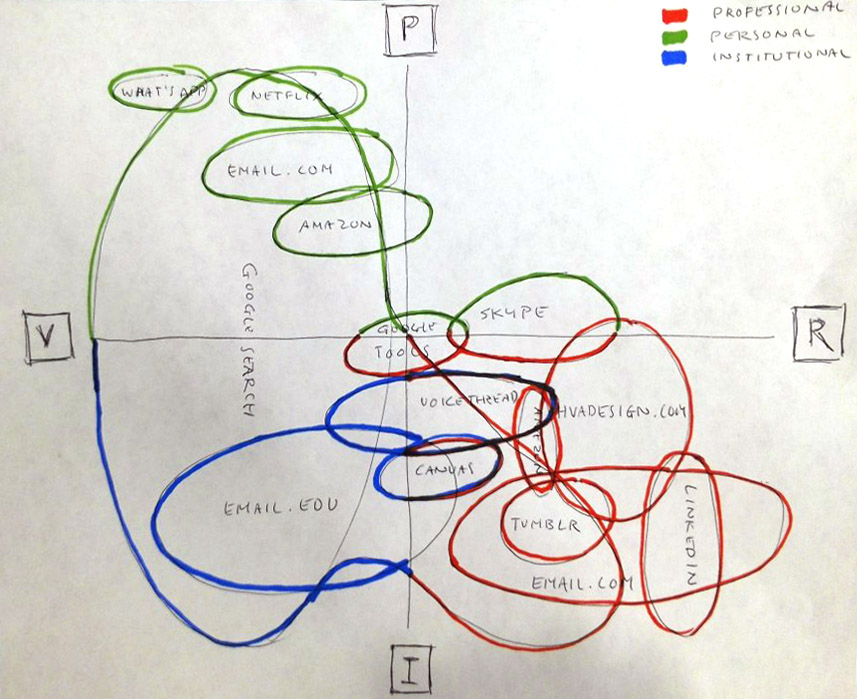

This notion of digital segregation goes beyond the physical and is often inherent in numbers 1,2 and 3 above whereby ‘learning’ and ‘work’ is perceived as being undertaken in physical locations (even when we are working with a digital device) and the digital is conceptually segregated off as a series of tools rather than a place in which that self-same learning and work can happen (a shift in thinking I’ve been attempting to influence for some time now).

I’m still thinking through DeL2015 and how we can build on the character of discourse that it fostered. It was a pleasure to host an elearning conference in which the ‘e’ took a back seat.