Designing pedagogy which coalesces digital and physical spaces

The keynote at our UAL Learning and Teaching day last week explored ‘Creative Learning Spaces’. As the images of new and co-opted spaces flashed by I started to think about how many of them would exist it it wasn’t for Wifi, laptops, tablets, smartphones and ultimately the Web.

Traditionally learning spaces would have been constructed around specific modes of knowledge transmission and proximity to knowledge. The main independent learning space being the library because it was useful to be adjacent to knowledge in the form of books.

It seemed obvious to me that the new physical environments we are designing in universities are a reflection of what the digital provides us and the way in which this has disbanded the geography of knowledge. Even so it was clear that this influence on physical spaces hadn’t been closely considered.

This comes about, I suspect, because the digital is commonly seen as a set of tools not a series of spaces or places. When I’m introducing the Visitors and Residents idea I’m careful to define ‘space’ as ‘any location where other people are’ or ‘any location where we go to be co-present with others’. It’s then clear that our motivation to go online is often very similar to our motivation to go to particular physical locations. The implications for teaching and learning are significant, especially when we take the example of students using connected devices in traditional face-to-face spaces such as the lecture theater.

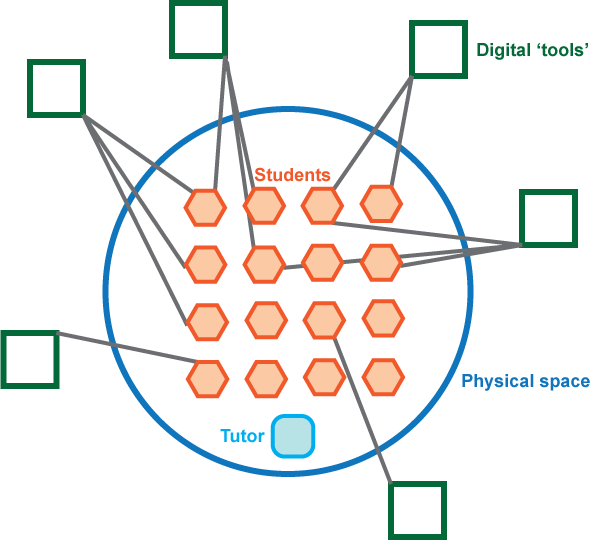

It we think in terms of the digital as a set of tools then our perception on the room might look like this:

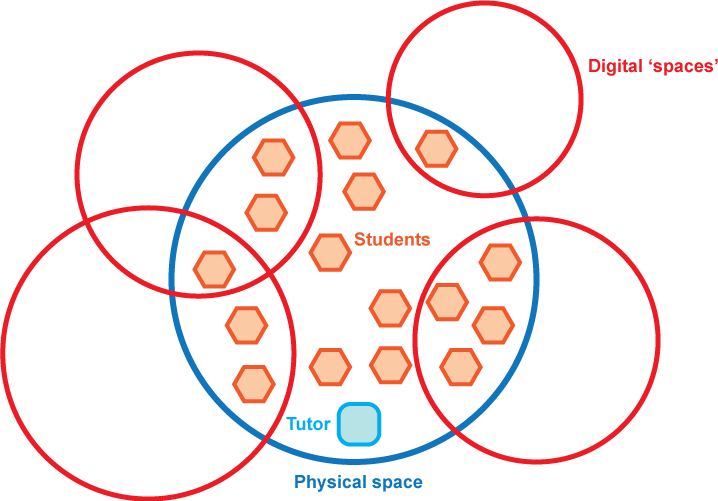

If we think of the digital as a set of spaces then it might look like this.

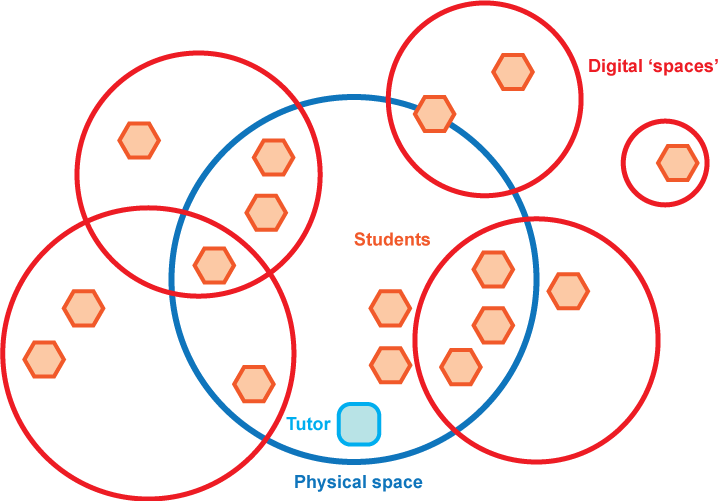

My view (if we exclude digital tools for a moment) is more along these lines:

This is because I tend to think in terms of presence rather than attention. As the tutor I could become preoccupied with how much attention students are paying to me or how ‘distracted’ they are by their screens. This is a very limited and unhelpful way of modeling the situation. A more interesting way of framing this is ‘where are my students?’ Just because I can see them sat in front of me doesn’t mean they are ‘in the room’. When they are looking at their screens they could be present in another space altogether.

This is where the digital/physical overlap becomes really fascinating. When we go online in Resident mode we are present in multiple concurrent spaces. We are always present in the physical world to a certain extent because we are embodied. However, we may be more present in the space on our screen than in the physical environment. This isn’t specifically a digital phenomenon, being multiply present is a human capability we are all strangely good at. How many times have you been transported into the world of the film or the novel you are gripped by? And yet when we conceptualise the digital it is often not along these lines. I suspect this is because the digital is still quite new culturally (even though it is well established technologically) so we don’t like the idea of the digital as immersive or captivating. For example, it’s acceptable to say that you ‘lost yourself’ in a book but to say that you ‘lost yourself’ in Twitter or on a website is still seen as suspicious or second rate (this is an extension of the books = good vs screens = bad problem).

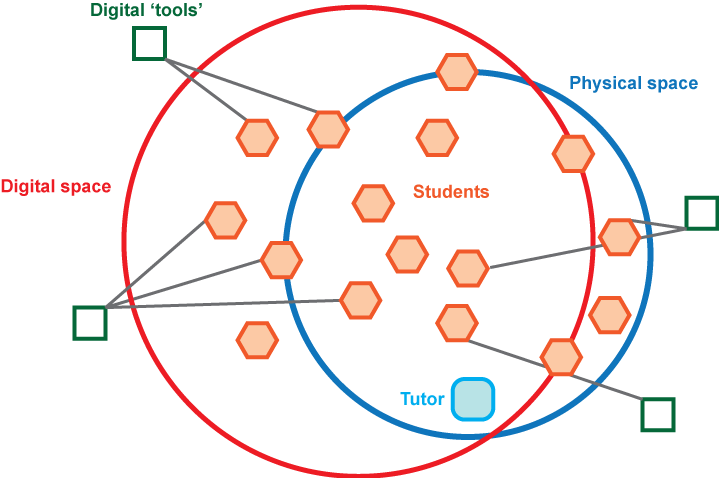

My response to this in teaching and learning terms is to design pedagogy which coalesces physical and digital spaces. Accept that students can, and will, be present in multiple spaces if they have a screen with them and find ways to create presence overlaps. This is different from simply attempting to manage their attention between room to screen.

A coalesced pedagogy would lead to this:

Here are a few suggested coalescent designs:

Discussing student work that has been created by students in the digital space when f2f.

A good example of this comes from our foundation course at Central St Martins in which students use our eStudio platform, Workflow, to gather research and to write reflections on their design plans. During f2f sessions student areas of Workflow are brought up on screen for discussion. Students can browse round their peers work in the platform and update their work during f2f time too. Obviously this could work well for any course in which the process of student work is captured as they develop it in an open or quasi-open online space. I think of this as a ‘soft-flip’ if we are talking in flipped classroom terms. Soft, because the f2f session is also bringing in the digital.

Online discourse while ‘in the room’

The best example of this is when a class or group join in with a live hashtag discussion. If the course has been designed in an open manner then it might be possible of the student’s themselves to promote and run a live discussion in this manner. The real advantage here is that a relatively small class can connect with a larger group which ensures a wider range of views and a good critical mass to drive discussions. The tutor can pick out salient points and convene a meta-discussion in the room in parallel with the hashtag discussion online. This is an event driven format which can be extremely engaging but it also has the advantage of being reviewed and reflected on in a more measured fashion after the f2f session.

Collaborative, critical, knowledge construction

This is as simple as putting a Padlet up on screen and then asking students to gather relevant resources on a topic into the space. They should also be encouraged to contextualise the resources they bring in. Once the Padlet starts getting crowded a f2f discussion can be started around how best to cluster resources into categories or sub themes. Again, the Padlet can be revisited after the session to support ongoing project work, acting as a co-constructed pool of resources or references.

Active knowledge contribution/construction

AKA a Wikipedia mini-editathon. Getting a room full of students to live edit specific Wikipedia pages to improve them or to create new pages. This is quite technical to get set-up as Wikipedia is likely to block sudden activity from a single place but Wikimedia UK are more than happy to provide support to get you started. They also have loads of good resources online to get you started on Wikipedia in an educational context.

There are just a few possible approaches that coalesce the digital and the physical around learning. For me the principle concept here is providing opportunities to be communal across the physical and the digital and to not get to hung up on the idea of collaboration. The communal is both easier to engender and potentially more engaging than the collaborative. It also allows for elegant lurking and doesn’t discount the notion of being present and engaged without ‘visible’ participation. Yes, students want access to the ‘stuff’ they need to get their courses done but unless we design communal digital spaces and coalesce the digital and the physical they will have a fractured and disconnected experience.