A recent Ed Tech/HE conference I attended opened day one with a high production value, inspirational, video. Traditionally at this event the opening video has outlined how technology is the future and will enhance everything ‘Empowering students to shape their destinies’ type stuff. (This is normally expressed through metaphor, and images of VR-ish stuff happening).

However, this year while the main message had a similar drive there was a new subtext. The video showed a young woman who appeared to be suffering from creative block, but through her own determination she broke through this, her ideas flourished, and she ended up inspired to paint and draw etc. I don’t recall much technology being involved beyond some laptop pointing and a bit of indistinct VR use. The human was central.

This seemed to be making the case for what, might be, unique about being human and how technology could support that. Another interpretation is that the video was actively defending humanness in an era of rapidly developing digital technologies. I’m sure this wasn’t the direct intention, but this theme did carry through the opening keynote from a Futurist who insisted, in the way that Futurists do, that we should try to imagine many possible futures. i.e. Not just the future that the technologist insist is inevitable on a hard dystopian / utopian split.

What do we bring to the table?

What I think I’m seeing is a post-AI shift towards a defence of humanity against technology. Or a gentler view might be that it’s an assertion of what is unique about being human – an attempt at defining what humans ‘bring to the table’. This theme isn’t new for example, in the nineteenth century Ruskin advocated for human centric values in the face of industrialised work which separated individuals from craft and nature. Harraway argued against the dehumanising drive of computational and technological ‘progress’ back in the 80s and the ‘what makes us human’ theme has been shot through literature for thousands of years (angels, Der Golem, Frankenstein’s monster, aliens etc.).

The new aspect for me is that this was an Ed Tech conference, not a symposium on gothic literature, a meeting of theorists. The organisation running the conference are techno-evangelists of sorts and have facilitated and funded a bunch of useful digital things for Higher Education in the UK. And yet their ‘this is what we value’ conference opening video could easily be used by the marketing department of my own university (The University of the Arts London). Our strap line is ‘The World Needs Creativity’. The strapline of the video could have been ‘Being Human Still Has Value’.

I wonder if we are seeing the culmination of a technological narrative which has been building for years. Wherein those promoting the tech must switch to promoting humanness and how the tech amplifies, rather than reduces, our ‘uniqueness’. There is a tendency here to imply a zero-sum principle to humanness: the more the tech can do the less it means to be human. This feels wrong to me and isn’t helpful in an educational context.

It’s more than the pointy bit – but it is the pointy bit.

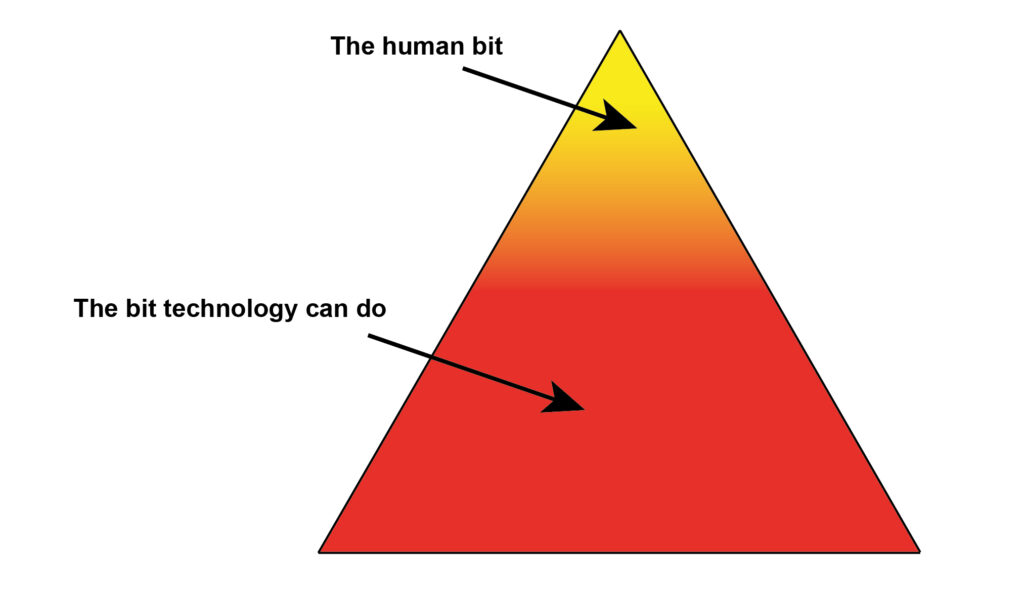

I mentioned a few blog posts back that, for me as an educationalist, the role of technology is to give us the opportunity to spend more time in the pointy, top-end, of the educational triangle diagram (you can pick any educational triangle diagram – they all imply that the pointy bit is what we are aiming for). Creativity, or something akin to creativity, often labels the pointy bit for example, in Bloom’s taxonomy the term ‘Create’ is used. In other frameworks it relates to agency and identity – various forms of self-determination and expression.

The downside of these triangles is that they imply ‘development’ is a kind of ladder. You climb your way to the top where the best stuff happens. Anyone who has ever undertaken a creative process will know that it involves repeatedly moving up and down that ladder or rather, it involves iterating research, experimentation, analysis, reflection and creating (making). Every iteration is an authentic part of the process, every rung of the ladder is repeatedly required, so when I say technology allows us to spend more time at the ‘top’ of these diagrams, I’m not suggesting that we should try and avoid the rest.

I’d argue that attempting to erase the rest of the process with technology is missing the point(y). However, a positive reading would be that, as opposed the zero-sum notion, a well-informed incorporation of technology could make the pointy bit a bit bigger (or more pointy). The tech could support us to explore a constantly shifting and, I hope, expanding, notion of humanness. This idea is very much in tension with the Surveillance Capitalism, Silicon Valley, reading of our times. I’m not saying that the tech does support us to explore our humanity, I’m saying it could and what is involved in that ‘could’ is worth thinking about.

It’s pleasant, in a quiet way, to see technologists reach for a simplistic only-the-pointy-bit version of creativity as the go-to concept when promoting a human-centric view. This is probably also comes about because the auteur-ish, ‘expressive’, aspects of a performative creativity make for good video visuals. My hope is that the new habit of defending, or promoting, humanness by technologists will lead to an increasing understanding of why ‘Art School’ values around not-knowing, risk, ambiguity, play and general graft are exactly what’s needed to continue to expand what it means to be human.