Prensky’s suspect notion of Digital Natives and Immigrants is predicated on levels of ‘innate’ comfort and skill with digital technology based on age. In contrast, the Digital Visitors and Residents idea is based on motivation-to-engage with networked technology.

Coronavirus has given millions motivation-to-engage, no matted their age, as social contact and educational provision has become almost entirely online-only overnight. We are all becoming ‘skilled’ with networked tech incredibly quickly, not because we are ‘native’ to it but because we have an immediate and obvious need. Our social and professional lives have become a parade of audio/video meetings and shared documents.

This highlights that the term ‘social distancing’ does not account for the Web and is better described as ‘physical distancing’. Many of us are now more Resident online than ever before and are therefore highly social (if not more social) during the quarantine.

Teaching during Coronavirus

The abrupt need to move face-to-face education online can be mapped to the Visitor – Resident continuum. At my university we have produced a ‘Core practice guide’ which highlights the need for a balance of ‘content’ (Visitor) and ‘contact’ (Resident) for/with student groups. Just as with the Visitor – Resident continuum one mode is not ‘better’ than the other and any effective online educational provision will use a mix of both. The important factor, in terms of the design of teaching, is how we connect together what we are providing across these modes so that the elements (resources, fora, webinars, recordings) build on each other and increase our student’s motivation-to-engage.

It’s not about the tech it’s about the teaching

It is also important to note that, as highlighted by the Visitor and Resident mapping activity, the type of technology does not inherently foster a particular mode-of-engagement. A poorly run online lecture (or webinar) will be less engaging for students than watching a recording or making use of some elegantly contextualised resources. My mantra is that if a synchronous (or ‘live’) piece of online teaching could have been a recording – from a student experience perspective – then it has little value beyond being an way-point in their week (see Eventedness).

Making online education engaging requires effective, well-structured , teaching way more than it does any specific digital platform. The most brilliant and fully-featured ‘webinar’ space will not counter a lack of framing activities and resources either side of the session. The same can principle be applied to text-chats, fora, quizzes etc.

If you like diagrams…

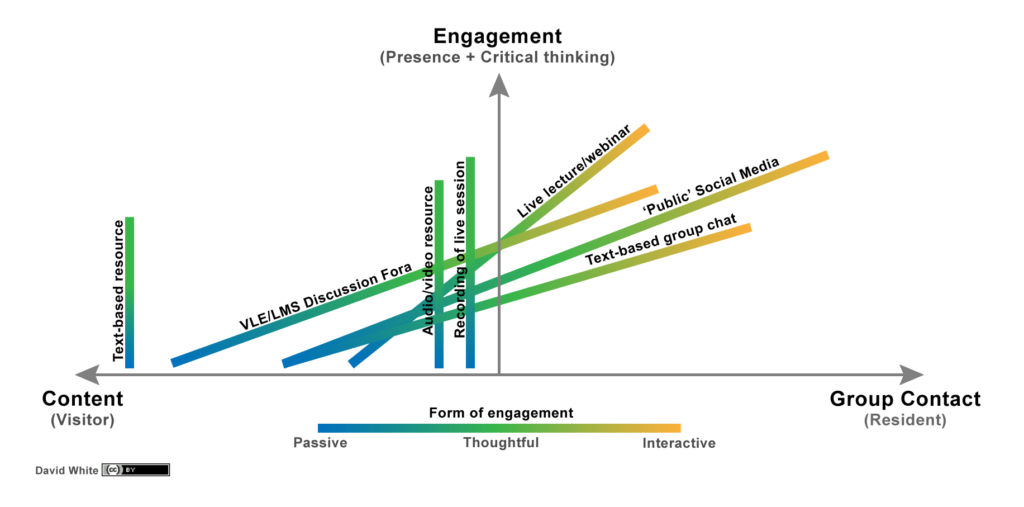

The following illustrates this point diagrammatically by showing that particular genres of digital provide the potential for certain levels/modes of engagement but that higher levels of engagement rely on the design of our teaching more than on how ‘immediate’ the tech experience might be.

The diagram is based on medium-to-large groups of students rather than small groups (less than 10) or one-to-one scenarios. Fostering engagement-at-scale is a central challenge for higher education and one which is crucial to consider as we transition to online teaching (and at any other time to be frank).

I’m defining ‘Engagement’ as a mix of social presence and active/critical thinking. The mix is complex but important, as one without the other can lead to either noisy-but-unthinking moments or thoughtful-but-distancing experiences. We want our students to develop their thinking *and* feel a sense of belonging.

Connecting it together

Any single technology or mode will not be enough to engage a group over a period of time. This requires connecting together a set of modes with a clear articulation of how they flow into one another. At my university we are promoting the use of a combination of Moodle and Blackboard Collaborate Ultra as these can be combined to effectively cover a huge range of Content – Contact. For example: read/watch a resource > respond to a relevant question in an actively facilitated discussion forum > engage with ‘live’ discussion in a webinar which is framed around the themes arising from the forum > write a reflection on the themes and the overall process to be posted to the VLE/LMS (or create image/audio/video with accompanying written reflection).

Fundamentally, one mode or tech is not ‘better’ than another. What is important is how we connect them as a learning narrative and how we communicate that narrative to foster engagement. This helps to ensure we provide opportunities which are mindful of the range of technical, geographical (time-zone), cognitive, social and emotional contexts/experiences of our students and teaching staff.