The University of the Arts London, where I am currently employed, has ambitions to widen access to creative education through fully-online provision. You can read about this in our university strategy.

This isn’t in-of-itself radical excepting that creative subjects have not, traditionally, been the focus of online development. The ‘standard’ subjects for online tend to have a more defined scaffolding of knowledge and learning – there are more ‘correct answers’. Examples include, MBAs, Computer Science and Nursing where learning and assessment can be (if required) perpetuated without the direct intervention of academic staff, up to the point that reflection or individual projects come into play.

Creative subjects tend to be built around the exact type of individual (or group) projects and critical reflection which require specific critical feedback and dialogue. At UAL almost all of our assessment is based on coursework, not exams, and much of this is evidenced through the development of personal portfolios. This is typically ‘Art School’ in nature and, as a colleague pointed out to me, heavily influenced by the traditions of Fine Art pedagogy. This is not to say that all creative subjects are a version of Fine Art. It’s that deeply held beliefs about what it means to nurture creative practice and thinking across many subjects are rooted in Fine Art style teaching methods.

Four foundations of creative teaching

There are many ways to cut this in how we might describe the foundational components of a Fine Art, or ‘Art School’ inflected education. Here is my, not exhaustive, overview:

- Teaching process, developing practice: ‘making’ skills, ‘craft’ or ‘technique’.

- Teaching theory and canon: The history of the subject. Learning the tools required to contextualise practice and develop a critical position.

- Teaching critical reflection: Applying theory to practice and vice versa, reflective writing, academic writing and research. Documenting (telling the story of) enquiry, ideation, process and realisation.

- Teaching-by-supervision to support individual and collective practice.

(As ever, if we have a broad view of terms like ‘practice’ and ‘process’ then these four points cover most subjects taught at a higher education level – especially if we categorise ‘academic writing’ as a type of practice)

Supervision-as-dialogue is central

In subjects where the focus is on developing a creative practice, supervision, often in the form of dialogue, becomes the foundation of the teaching & learning approach – the ‘signature pedagogy’. Most academics at my university would see this as crucial, almost axiomatic. If we are honest in our proposition that students can interpret project briefs/assignments creatively, then teaching must mold itself around the variation in those responses, it can’t be generic, it has to be thoughtful. Is a Fine Art course without dialogue Fine Art? It certainly doesn’t feel like it.

I’d argue that the supervision model of teaching is the primary design consideration when developing accessible online provision. Developing workable models of supervision is at least as important as responding to concerns around materiality and physical making practices. The latter can be re-situated, up to a point, to be local to the student whereas supervision is hard-wired into the identity of creative education.

For some, supervision is by definition the soul of the course. Dialogue, structured or serendipitous, with experts (academic and technical) is possibly more important than access to specialist equipment and spaces. When students describe ‘the course’ they are most likely to mention moments of real-time supervision coupled with stories of personal, or group, practice. They are less likely to mention text-based feedback even if that was influential. This could simply be because embodied, live, moments tend to be easier to recall?

Supervision vs access

The uncomfortable aspect of accepting this is that a supervision model of provision is in tension with access in a number of ways:

- Supervision requires significant staff time which risks reducing access in terms of affordability for students.

- Supervision is commonly framed around moments of ‘live’ (synchronous) dialogue which is difficult for students with busy lives, or across time zones, to frequently engage with.

- One dimension of increased access is greater student numbers. In a supervision model the limiting factor will quickly become the availability, or even existence, of teaching staff with the right balance of teaching and creative-practice experience.

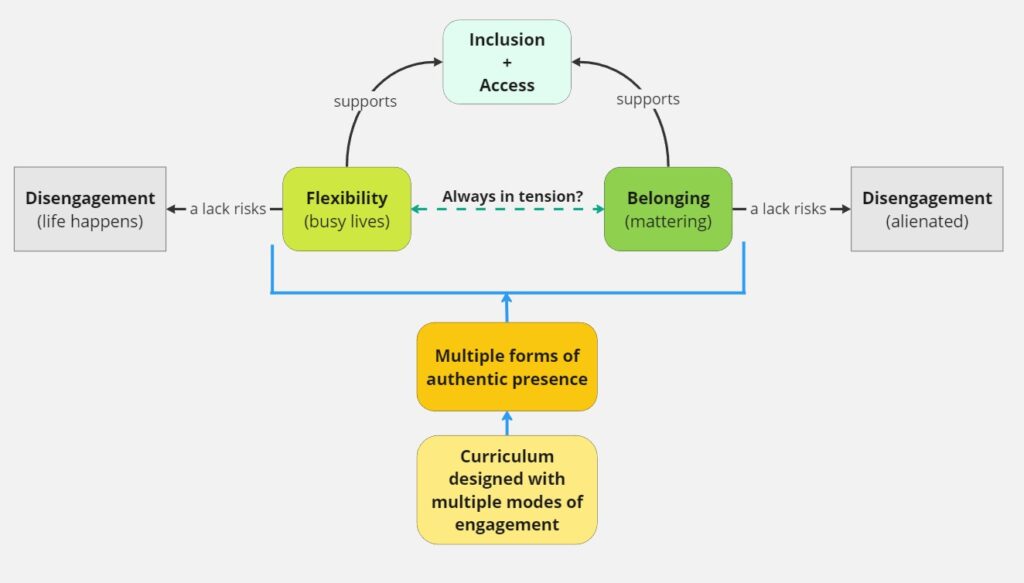

So we end up with a scenario where reducing the amount of supervision in creative education provision is not just a curriculum design choice, it’s an erosion of what we believe the subject to be and a dilution of what some students believe they are paying for. On the other hand, predicating any course (and here, I’m going beyond creative education) on supervision risks attenuating access across a number of dimensions.

The powerful cultural/educational position of supervision is, I suspect, what underpins student demands for moments of ‘live’ teaching (in-building or online) which are then poorly attended. Students and staff need to know these supervisory, or live, moments are happening or they feel the course ‘doesn’t properly exist’. However, when students are not in a position to attend, or the inconvenience of attending ‘live’ is outweighed by the sense that attendance is not contingent on success, everyone feels unsatisfied at some level.

The importance of acknowledging ‘non real time’ supervision

In response, I’m not suggesting that the supervision model of teaching is a problem to be solved. The troublesome aspect is not the practice of supervision but that it is too closely associated with ‘live’, or real-time, teaching. This is often cemented by legal and regulatory approaches to ‘contact time’ – as I’ve discussed before.

It’s of note that the coupling of supervision and ‘live’ doesn’t accurately reflect day-to-day practice given that dialogue and feedback is often via text in the form of online messages, comments, annotations etc. In essence, the practice of supervision has adapted to incorporate the not-real-time opportunities of the digital environment but our conception of supervision seems stuck in a previous era. We need to accept, or rather acknowledge, that much of our dialogue takes place in non-real-time forms which are more varied than an epistolary or summative feedback.

Unfortunately this means that we underestimate, or fail to identify, the actual volume of teaching which takes place. This inability to ‘see’ teaching as anything other than ‘live’ is partly responsible for creating unsustainable work loads. A course as documented and validated is likely to not capture this middle ground between ‘contact time’ and ‘independent’ hours, except perhaps as a vaguely defined form of administration (sometimes this also falls under ‘pastoral’, ‘community’ or ‘support’ type labels).

Less ‘live’ and more ‘supported’

Extending our definition of supervision to incorporate non-live forms of dialogue is crucial if we are to balance subject and access. My team is defining this as ‘Supported’ teaching. A mode of supervision which provides flexibility for students and softens the line between ‘Live’ and ‘Independent’ teaching and learning.

The question I’m exploring is how much ‘live’ can become ‘supported’ in online provision before the nature of the subject itself is changed. Or, to put it another way, to what extent is the teaching mode and the subject itself intertwined? If we don’t understand this entanglement then any design process where academics are famed as ‘experts in the subject’ and others are experts in ‘learning’ could grind to a halt. If particular teaching methods are part of the fabric of a subject then we can’t re-design teaching without re-imaging the subject.