A couple of blog posts ago I suggested that our response to AI is pushing us into a dangerous model of humanness.

“There is a tendency here to imply a zero-sum principle to humanness: the more the tech can do the less it means to be human. This feels wrong to me and isn’t helpful in an educational context.”

https://daveowhite.com/pointy/

I explored this zero-sum idea at a recent talk to staff at Kingston School of Art. To support my line of thought I picked up a quote in a post from Tobias Revell. The quote refers to Science Fiction (SF) but as Tobias points out, our current futures are largely based on SF thinking.

“I would argue, however, that the most characteristic SF does not seriously attempt to imagine the “real” future of our social system. Rather, its multiple mock futures serve the quite different function of transforming our own present into the determinate past of something yet to come.”

Progress versus Utopia; Or, Can We Imagine the Future?

Fredric Jameson, Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2, Utopia and Anti-Utopia (Jul., 1982), pp. 147-158 – via https://blog.tobiasrevell.com/2024/02/07/box109-design-and-the-construction-of-imaginaries/

Questioning the future

I’m not a futurist but when it comes to emerging technologies it is useful to question what model of the future we are working with. How that is shaping our present and how this is, in turn, painting humanness into a corner. In short, the specific technology is less problematic than version of the future being sold.

The model of the future promoted around AI, and picked up in education, contains many assumptions and tacit implications. The main one being that once AI systems reach a certain level of complexity and/or have enough data to feed on they will reach ‘Artificial General Intelligence’ (AGI).

“…a type of artificial intelligence (AI) that can perform as well or better than humans on a wide range of cognitive tasks”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_general_intelligence

An image of intelligence entering the station?

A quick scan of the Wikipedia article on this makes it pretty clear that we are nowhere near that and there is little evidence that AI systems are actually on that path. However, the assumption that this has already happened or that it is inevitable is what is behind the zero-sum model of the future.

When I see articles with ‘this feels like AGI’ in them it reminds me of the train entering the station story from the early days of cinema. People allegedly panicked when they saw the film and cinema was, and is, a technology with a massive impact but what people saw was an image of something and not the thing itself.

We are not computers and intelligence is a sibling of mystery

Some of what drives this is a collective forgetting that the brain is not a computer and that that idea is merely a metaphor. So, building a hugely complex computer can only ever make a metaphorical brain. Or as Mary Midgley argues in Science as Salvation, the problem isn’t that we are operating with myths, the problem is that we have recategorised myth as fact, and therefore inevitable.

Add to this that there is no agreed definition of intelligence, and everything suddenly becomes very murky (Helen Beetham writes elegantly on this point).

My personal view is that we are extending the ‘Chinese Room’ in a manner which is impossible to understand (the way a neural networks operate in programming means that it’s not possible to deduce the process back to any kind of human-readable form). Our working definition of intelligence is then an absence or an ignorance, in that it’s a notion we ascribe to that which remains a mystery. This is another salient factor driving the zero-sum model of the future.

The problem with the pointy bit

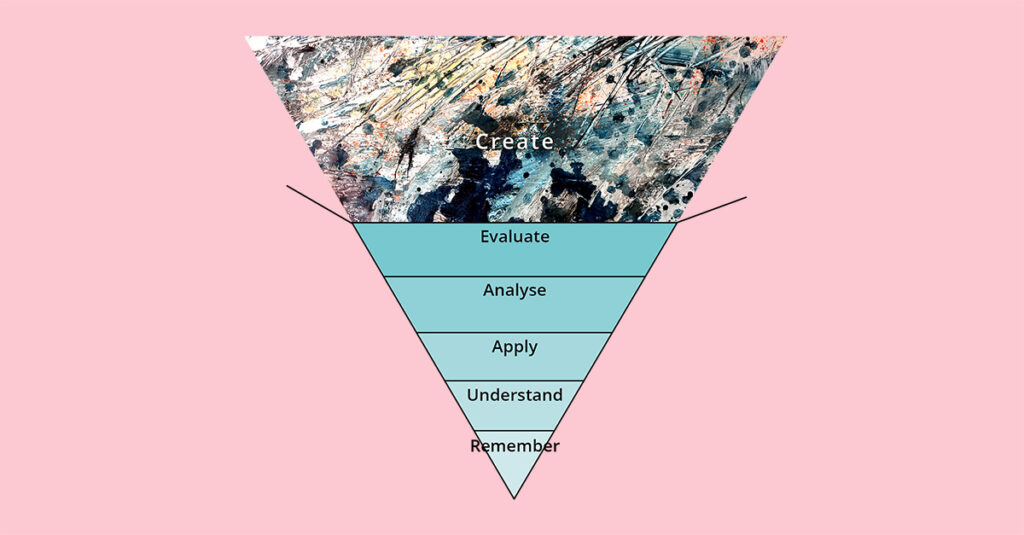

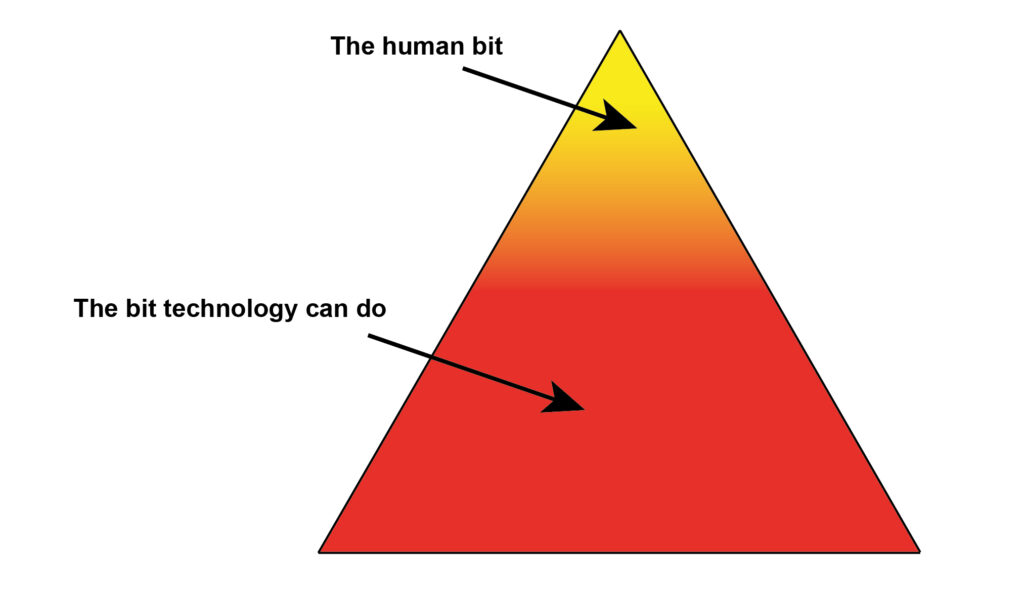

When I first pointed out the zero-sum problem, I helpfully provided a bad diagram.

The quick version of this being that many educational models are triangle shaped and the ‘higher order’ learning is in the pointy bit, often labelled as ‘creativity’ or something similar. The reason I called the diagram bad is because it perpetuates the zero-sum model of the future. Technology might help us to move into the pointy bit faster, but the diagram implies that the strictly human nature of pointy bit thinking and learning is small and constantly being chipped away at.

This is the problem with triangles, they get progressively smaller at the top until there is no space left at all. If we go with Blooms Taxonomy here, then it implies that human creativity is finite as if it was possible to complete being creative. Clearly this isn’t what is mean by the diagram, but these implicit notions are powerful and persistent. Having given this some, let’s go for a walk and have a think, time – I came up with a brilliant idea which it turns out a bunch of people have had before.

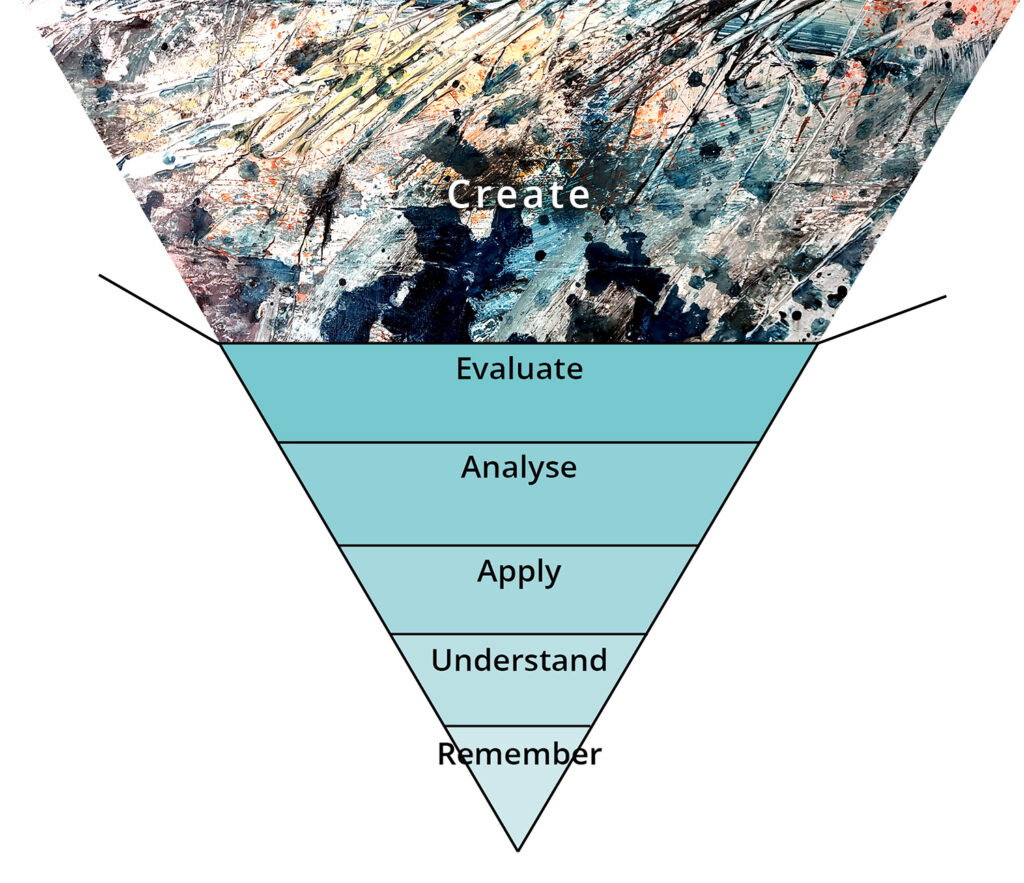

Flipping Blooms for unbounded creativity

What if we simply turn the triangle upside down rip the lid of it off (this lid ripping is my contribution).

What if remembering, understanding, applying etc. are what you dip into to support a process which starts with creativity? That would certainly chime with how students at the University of the Arts London work. Significantly, what if creativity wasn’t a finite pointy bit but was a jumping off point into a space which, by its very nature, cannot be bounded but opens out into unknown possibilities? Moreover, it could be argued that the relative educational weighting (if we go by the size of each slice) is a better reflection of where the educational emphasis should be in an era of information abundance and AI.

Certainly, a model of the future based on a lidless upside-down Blooms Taxonomy would be less fearful than the one we are currently being sold. In this lidless future, emerging technologies become a vehicle for us to explore the ever-expanding outer reaches of creativity rather than the thief of our humanness. I seem to remember that was the model of a technological future before technologists became our new high priests and I’d argue that the move to the zero-sum model is a failure of secularism (a topic I find fascinating but which is too big to get into here).

Not my idea

As I said, I wasn’t the first to up-end Blooms. That idea I’ve managed to trace back to around 2012 and relatively early discussions of the flipped classroom. For example this via Shelly Wright, which I traced back from this Open University post by Tony Hirst.

The OU post also links to a piece from Scott McLeod for around the same time which delves back into the thinking behind Blooms Taxonomy and how it was never mean to imply ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ forms of learning nor that each slice should be seen in terms of ‘amount of learning’. Given this, I suggest that putting it into a triangle was a spectacularly bad idea which, as Scott points out, has perpetuated a pretty impoverished approach within formal education. Hopefully, my lidless upside-down version of Blooms goes someway to redress this.

Embracing a squiggly future

Ultimately my favourite antidote to the triangle is the squiggle. My favourite struggle of all time being Tristram Shandy’s diagrams of his approach to storytelling in a novel by Lawrence Stern.

In the novel Shandy gets side-tracked so often that he never even gets born in the telling of his own life-story. And yet, somehow we learn an enormous amount about him through this wandering and the story is hugely entertaining. For me this is a fabulous touchstone for the principle of assessing the journey and not the output in education.

The-squiggle-as-process is a much more honest metaphor for learning than the rigour of the triangle because a squiggle is messy, sometimes beautiful, and everyone takes a different route. We squiggle all over Blooms as we learn and we potentially squiggle our way out into the unknown beyond the lid of upside-down Blooms. So here’s to a creative, squiggly future in which education does not fear technology and our humanness knows no bounds.

Patrick May 17, 2024

Great post! The last part reminds me of Newman’s design squiggle.

https://thedesignsquiggle.com/about