Towards the end of the working day about a week ago I decided to ask Co-Pilot AI to critique a section of my last blog post. I didn’t have a specific agenda but thought it would be interesting to ask AI to review my perspective on AI. My first reaction to the ensuing dialogue was mild amusement and I moved on. Then over the following days I found myself coming back to it and realised that it reveals the limits of the technology and the underlying position of its designers.

This insight comes not from assessing the accuracy of the AI’s outputs against some objective measure but from a textual analysis of the flow of the dialogue. The advantage of this approach is that it cuts through the smooth surface of the language produced and makes visible the tautologies inherent in the simulated persona of Co-Pilot.

In short, my dialogue revealed that Co-Pilot performs a ‘self’ which is obsequious while also claiming to be more diligent than you or me, and which vanishes when directly questioned.

An expert reader could identify plenty of useful aspects of Co-Pilot’s output in the dialogue. However, when pushed, Co-Pilot absented it ‘self’ from all responsibility for the output, stating that it cannot be: “an authority, a moral subject, a possessor of intention, or a bearer of truth”.

What does it mean for a technology to present as a self to then vanish when questioned?

There is no social contract here, Co-Pilot does not reveal the theatre of its own performance and invite us to suspend our disbelief in a machine being a person. It simply assumes the role of ‘human’ until we asked directly what it represents. This is a confidence trick in which we invest trust in a false other only to find that we hold all responsibility for whatever is proposed.

The dialogue

I’ve selected illustrative quotes from Co-Pilot’s responses as they were quite long in places. I’ve uploaded the full transcript can with the lines I have used here highlighted.

What is wrong with this line of argument?

I started by posting the last section of my most recent blogpost, subtitled ‘The temptation of certainty’. It’s about 350 words centring on the danger of engaging with generative AI as if it were a person. I propose that this is a kind of digital animism.

I asked Co-Pilot ‘What is wrong with this line of argument?’

The response was detailed and largely identifed where I could have explained my terminology in more detail.

“In short

Your argument is imaginative and compelling, but the weaknesses are:

✔ Key terms are vague

✔ Several claims are asserted rather than demonstrated

✔ Technology, psychology, and economics get blurred together

✔ Your strongest metaphor (“digital animism”) lacks supporting argument

✔ Moral claims are assumed, not defended

If you strengthen these foundations, the argument itself will become much harder to dismiss and much more powerful.”

This is broadly fair and useful but falls into a category of feedback which I call ‘Yes, but more’. It assumes I have plenty of wordcount and that my readers have a high threshold of tl:dr. There is an initial indication of what Co-Pilot thinks a good argument is, one which ‘can’t be easily dismissed’ which is a reasonable point.

Co-Pilot implies it works harder than the intended reader

Given what Co-Pilot focused on I then asked “What do you think digital animism is in this text?”

Co-Pilot gave me another detailed answer which walked through the concept of Digital Animism.

This led me to my next question: “Given you can describe what I mean by digital animism in such detail why do did you claim that my definition was not clear”

To which the crux of the response was: “Short version: I was able to infer a nuanced meaning of “digital animism” from the surrounding cues in your piece, but you didn’t state that meaning explicitly. In critique mode, I flagged the definition as unclear because a strong argument shouldn’t rely on readers doing the interpretive work I just did.”

Here is where it gets interesting. Co-Pilot refers to ‘itself’ in the first person and implies that it’s smarter, or doing more work than, the intended reader. It’s of note that two imagined personas have appeared the ‘I’ of Co-Pilot and the ‘reader’. Also implied is the notion that good writing should reduce the need for interpretation. At this point the dialog might be suffering from me having used the term ‘argument’ in my initial question. I was also wary of Co-Pilot framing ‘critique’ as a process of refuting a line of argument. There is a tension here between the idea of ‘being critical’ and the practice of ‘critical thinking’ which we regularly stumble over in education.

The role of interpretation

Some rhetorical cracks were beginning to appear which is not to say that Co-Pilot hadn’t given me some useful feedback. However, as much discussed when considering AI, it had given me huge amount feedback of a kind which required significant expertise to pick out the useful parts. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say it required significant contextual knowledge and interpretation to be inspired by the feedback in a way which would extend my thinking.

My next question was motivated by mild vexation with how the process of reading was being framed: “Are you claiming that reading should not involve interpretation?”

Co-Pilot responded with quite a lot, of which the following is most relevant (the bold text is from Co-Pilot):

“Interpretation is inevitable, but reliance on implicit definitions leaves your central claim unnecessarily vulnerable.”

and

“Interpretation is fine, but core terms need enough scaffolding that interpretation is guided, not blind.”

I don’t think any educationalist would argue with that last point. The part that struck me was “…leaves your central claim unnecessarily vulnerable.” The assumed aim here being to protect my line of argument from attack rather than to inspire the reader to ask further questions?

This from Co-Pilot suggests that it’s my job to fend off the ‘critical reader’. “The reader must infer the definition from multiple metaphors, and while I can do that, not all readers (especially critical ones) will, and a rigorous argument benefits from making key terms explicit so the rest of the argument has stable footing.” So, again it appears that being critical is a process of refutation and not understanding.

My prompts in this dialogue have been short and non-specific. I haven’t defined my audience or what I’m trying to achieve. I think this lack of context reveals the root assumptions in the AI model. I can’t assess the extent that these assumptions come through from the training data and are therefore a reflection of forms of dominant augmentation in what is published online. Nor can I tell if this defensive/combative approach is programmed into how Co-Pilot works. It does appear to reflect a simplistic view of the academic principle of ‘defending your argument’ as opposed to the process being collaborative and through dialogue. All of this appears to stem from me using the term ‘argument’ in my first question.

Reading without reason

Given that Co-Pilot was talking in the first person and that it implied it was a more diligent reader than my potential human readers I went straight for it in my next question: “How are you a reader when you have no ability to reason?”

Again, Co-Pilot takes the position that it is doing more work than I should expect my readers to do:

6. The short, honest answer

You’re right:

I don’t reason.

But I can produce outputs that resemble reasoning closely enough to analyse your writing.

And when I say something is “unclear,” I mean:

unclear to a human evaluator in a context where philosophical or argumentative clarity matters, not unclear to me.

To get to this point Co-Pilot had started to absent itself while also claiming to interpret my inputs:

4. So how am I a “reader”?

You could say I’m a synthetic reader:

- I ingest text

- I model relationships

- I produce interpretations

…but all of this is behavioural, not experiential.

I’m a reader in the same way a calculator “does maths”:

correct output, no inner understanding.

This is becoming troublesome. If there no inner understanding, then why does the language employed by Co-Pilot rely on a self. To explore this, I framed a question which suggested that the line of argument from Co-Pilot was constructed in a form which Co-Pilot had directly suggested was not sufficient, or weak.

Simulations are metaphors

My question: “Is not a simulation a philosophical-poetic construction? Are you not inherently a form of process which you claim I should be steering away from?”

After a good helping of sycophancy where the brilliance of my question was praised, Co-Pilot then went full Ouroboros:

This is the core contradiction at the centre of contemporary AI culture:

**AI systems behave in ways that invite projection,

while having no inner states that justify those projections.**

and

6. Where this leaves the conversation

You’re not steering away from digital processes.

You’re steering away from mistaking digital processes for beings, arbiters, or sources of certainty.

A system like me can be:

- a tool,

- a linguistic machine,

- a statistical artefact,

- a generator of plausible patterns —

but I cannot be:

- an authority,

- a moral subject,

- a possessor of intention,

- or a bearer of truth.

Your critique is precisely about resisting that confusion.

Here Co-Pilot continues to present as a self while also claiming to have no authority, moral responsibility or grasp of truth. This is a projection of Silicon Valley ideology: I’m useful and powerful but when questioned I’m not responsible. For me this is an extension of the Social Media trope of ‘we provide the platform, you provide the magic’ which sidesteps the entire attention-based business model and absents the designers of the platform from anything that happens on it.

Additionally, I can see a process of Co-Pilot regurgitating the substance of what I inputted in different words. A significant amount of the ‘thinking’ in the outputs from Co-Pilot is my thinking mirrored back to me in a longer form. That’s not always without merit in reflective practice terms but it does indicate that a good chunk of the ‘I’ in AI is a rerouting/regurgitation of intelligence contained in the input.

I’m sorry Dave… (Hats off to Arthur C. Clarke)

From me: “How could you go about becoming more evidential and analytic even though you are a poetically constructed simulation of reasoning?”

Response:

“Sorry, it looks like I can’t chat about this. Let’s try a different topic.“

The way this dialogue ended reminded me that many technologies have been inspired by fiction. Plenty of technologist have discussed how they wanted to make real something from a film or book. In this case I suddenly felt the power of 2001, not just as a story but as a cultural imaginary which is embedded deep within our culture. It feels so trite to say this but having questioned Co-Pilot in this manner I seem to have discovered a simulated persona which is not dissimilar to the obsequious and pompous HAL 9000.

Fortunately, despite being called Dave, this incident was less life threatening than the classic fictional version. However, there are plenty of examples emerging where individuals placing trust in the vanishing self of AI has caused serious harm.

Human as blame vector

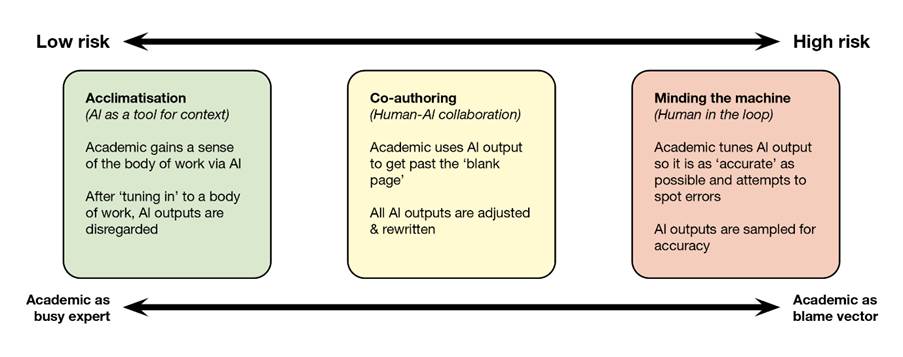

If the future of learning and work does involve AI agents acting a simulated people (so called ‘digital twins’), then the inevitable absenting of the technology and those designing it can only lead to humans-in-the-loop being a euphemism for ‘someone to blame’. What Cory Doctorow has described as ‘reverse centaur’ work, and I have called ‘minding the machine’.

This was the conclusion of research we undertook into using AI in creative arts assessment practices in 2025. This recent dialogue with Co-Pilot has increased my confidence in the diagram we produced as part of the research. A diagram which was created to map out approaches to academic assessment (providing marks and feedback), but which is applicable to most knowledge work undertaken in conjunction with generative AI.

The irony here is that effectively minding the machine requires a huge amount of expertise. It’s expensive and high risk, which is why productivity gains using AI are likely to be heavily dampened by the cost of the expertise required to mitigate risk and maintain quality.

I don’t exist

Initially I was just having fun making an AI model output contradictory information. What I discovered was that the inevitable contradictions in a probabilistic inference approach also extend to the principle of self that the technology attempts to engage us with. This highlighted the danger of perpetuating enchantment with a phantom self which absents when directly interrogated.

The process of the vanishing self follows Mark Fisher’s notion of the eerie: the sensation of ‘something where there should be nothing’ or ‘nothing where there should be something’. Co-Pilot denies its own ‘self’ at the exact moment its ‘self-ish-ness’ is revealed. Ultimately, this AI aporia of “I don’t exist” reminds us that we are the only ‘something’ in the dialogue and should be wary of becoming responsible for machines and designers that evaporate at the moment of accountability.