(…and why there’s no such thing as ‘information-seeking’ for school students)

This month Jisc published a report I wrote with Joanna Wild about secondary school student’s experience of technology for learning. The report is part of The Digital Student project and makes recommendations to the Higher Education sector about how to meet and manage incoming student’s expectations of the digital environment.

The emphasis in the report wasn’t on the technology the schools owned but on how they incorporate it into the day-to-day curriculum. Generally what we found was that within the classroom digital technology is used in the service of making existing pedagogical processes more efficient rather than as an opportunity to engage students in new ways – an example being the frequent, non-interactive, use of PowerPoint by teachers. This appears to be an effect of the training available to staff which generally concentrates on functional skills, neglecting discussion of how technology can be effectively incorporated into teaching.

I’ve spent the last few years discovering how students go about learning now that the Web exists. Given that I was fascinated/bemused by the apparent disconnection between the classroom and how homework gets done. It’s truly strange that homework is set by schools with the assumption that the Web will be used to complete it but without admitting this fact institutionally. This is to the extent that many students don’t even receive textbooks for key subjects.

So on the one hand the Web is talked about as a place where you have to be wary of the quality of information and on the other it’s absolutely integral to successfully undertaking your studies. This feels to me like the start of The Learning Black Market for students and in theory puts them in a dissonant situation as they attempt to bridge the divide between the classroom and the way they complete homework. I say in theory because the quality of information to be found online will be very high and because they won’t be required to cite sources for much of their school career. So in essence the system works but not by design – it’s disconnected and I don’t see much evidence of it being brought together.

The problem here is more to do with ‘knowing’ than with technology. I explored the notion of a loss of ontology when discussing the relationship between Wikipedia and education and I believe that this is a significant effect of the disconnect between the classroom and home. Students are developing basic approaches to finding and using information online without much support from school. Obviously the aim of the game is to complete your homework as quickly as possible and then go out and play football with jumpers for goalposts (yes, yes, I know).

The sheer efficiency of the Web means that students can leap to a highly focused answer online without having to build a knowledge map of the discipline territory. In some senses there is no process of ‘information seeking’ – simply type a question into Google and the answer will appear. Crucially (and I’m happy to labour the point) the information ‘discovered’ will be good enough/excellent so raising eyebrows in a library-style fashion about this approach not-being-proper is not relevant.

This then shifts the task in hand to masking the fact that most of your homework can be completed with the use of one super-convenient source that appeared in the top three links returned by Google (often Wikipedia). From what I’ve seen that means ‘how to delicately rewrite stuff I’ve found online so I can’t be accused of copying’. (…to be fair that’s the same as it ever was in school but it’s more efficient and so more prevalent with copy and paste)

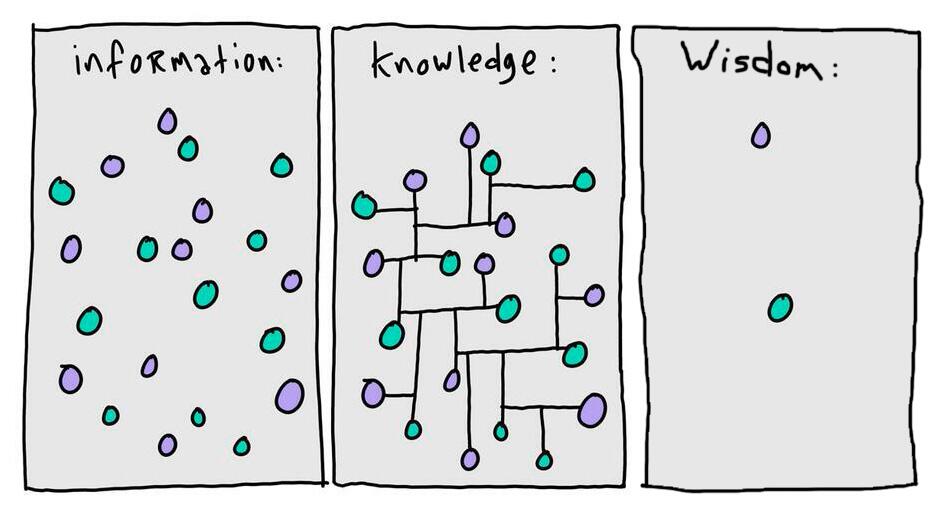

This (slightly trite) diagram helps to illustrate what I see as the challenge formal education needs to respond/adapt to. Historically the connecting lines that evolve ‘information’ to ‘knowledge’ (I’d use the term learning myself) were partly formed by the process of information seeking -the effort required to piece together understanding by locating and trawling through books. The connections that build an ontology of information were a side effect of this relatively inefficient process. Or, in a lesser way, they were implicit in the structure and layout of your textbook. Now that information seeking is all but dead these lines are less likely to be formed, especially when doing homework. Wisdom isn’t my specialty but I’d argue that deep understanding comes from making connections and not simply discovering scattered answers.

This is the central disrupting effect of the Web on formal education, a disruption of pedagogy and epistemology. Our response should be to bridge the disconnect between the classroom and homework by designing curricula that explicitly accepts the Web is already central to how education operates and is a legitimate source of information.