Like most of us I’ve been involved in many pandemic conversations about what we have lost, the moments that worked well and what we’d like to hold on to.

Having given this much thought I believe that what we have been missing the most is not only being together physically but also the inherent spatiality of physical co-presence. Our ability to connect with each other and to learn is deeply reliant on social and conceptual maps – where things are located relative to each other – and maps are by their very nature spatial.

Our mistake has been to assume that if we can see each other’s bodies then we must be together in the same place.

What the tech doesn’t give us

The pandemic ripped away our opportunities to be physically co-present and we immediately turned to our technology in an attempt to repair this loss. We wanted to ‘see’ each other and feel connected in meaningful ways. The result was a sea of live video feeds, stacked in shifting grids. This was certainly useful for attempting to read emotion and perhaps attention but it felt thin and lacking, insubstantial, often alternating and exhausting.

The technology appeared to be giving us a version of what we had lost and yet it never felt quite right.

Disembodied images

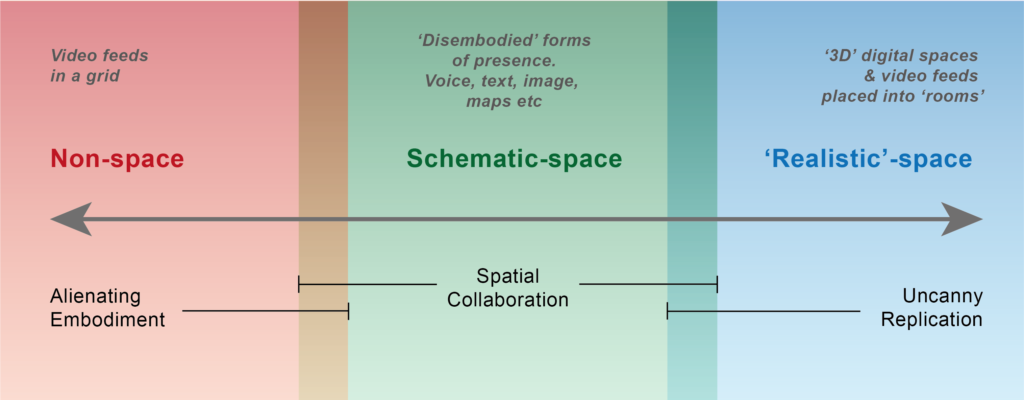

We could see bodies but felt disembodied. The reason being that there is no sense of space or location. What is the location of Zoom/Teams/Skype meeting? It’s a non-space, it’s only a time and a list of people – at best its location is ‘on-screen’, which is no place at all.

The grid of faces is constantly shifting and laid-out differently on each person’s screen. Add to this the fact that we see our own body reflected back at us and we are forced to ask ‘Where am I?’. I can’t be ‘with’ the people I see on screen because I’m constantly reminded by the digital reflection of myself that I’m in my room at home, hunched over a computer.

Attempts to mitigate this detached feeling simply throw us into the uncanny valley. The ‘together’ modes, where our images are placed onto a static picture of a room ‘side-by-side’ just serve to remind us of what we have lost. There I am looking back at myself – a digital, synchronous doppelganger floating alongside images of people laminated onto a two dimensional surface like samples on a microscope slide. The result is a distressing panopticon where we are trapped under the omnigaze of all, while somehow not ‘seeing’ each other or feeling any meaningful presence. It’s psychologically and socially exhausting with very little sense of connection.

Skeuomorphic presence

This situation had arisen through ‘skeuomorphic presence’. As with most technological shifts the initial phases reflect that which went before. We start by replicating the modes we know in new contexts, before we move on to reimagining ways of being. As such, we insisted on the connection between bodies, co-presence and togetherness. And yet, what we found is that attempts to ‘mirror’ the body into the digital feel unreal.

We can read emotion on the face, but that face is a simulacrum. We desperately tried to forget that the camera is a special effect, an image, a process of disembodiment like the floating smile of the Cheshire cat. We clung onto the body to such an extent because we assumed, as with physical co-presence, that putting bodies side-by-side must generate a place but this is not the case and it’s what we need to design back in.

Schematic presence

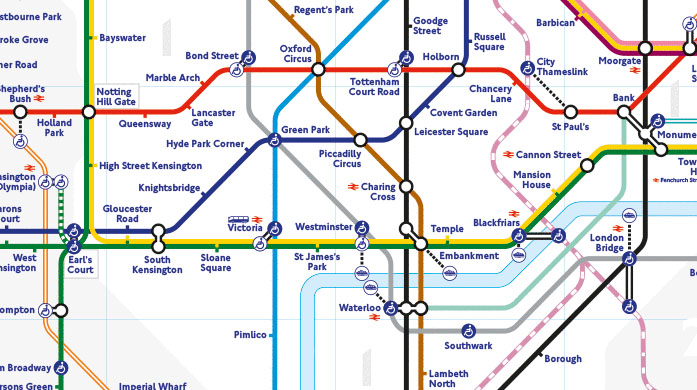

The temptation then might be then to create a more ‘realistic’ and volumetric digital space by moving towards three dimensional imagery, such as gaming*, and further still via ‘immersion’ with VR headsets and haptics etc. While this has many merits, I see it as a red herring which can easily throw us back into an incredibly intricate and exclusive uncanny valley. What I propose is not reaching for the ‘real’ but building on our spectacular ability to work with the map not the territory – to be able to operate in an imagined spatial-conceptual, or topological, manner.

A great example of this is the London Underground map. It allows us to understand the ‘place’ of London schematically. It is not attempting to be ‘real’ and in doing so, gives the most relevant information we need to spatially and conceptually navigate the system it represents. So what might be the equivalent of the Underground map for our online lives?

Creating maps to build shared locations

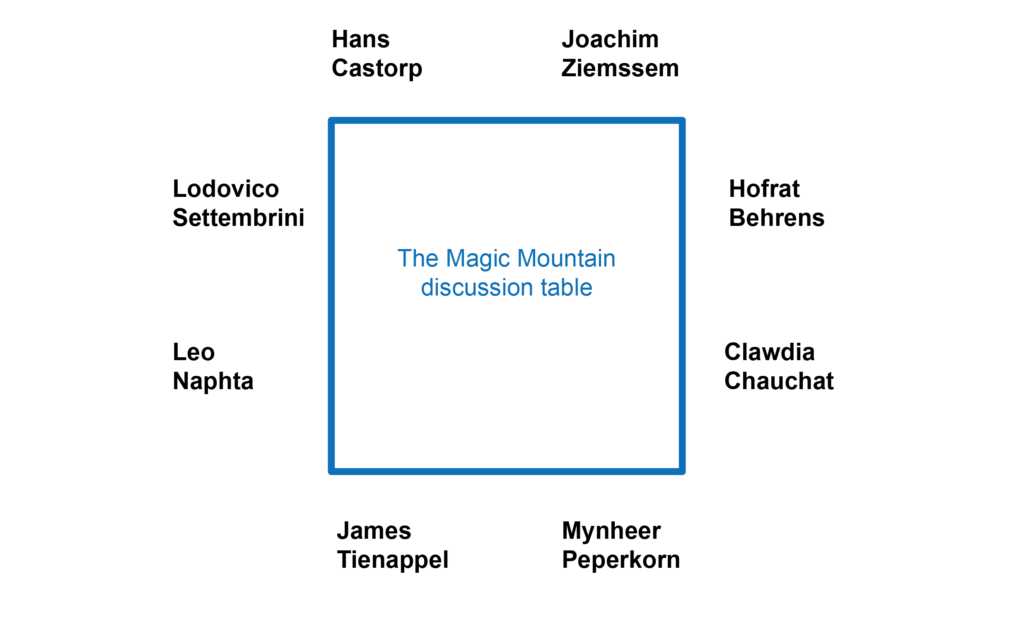

A couple of years ago I was helping to run a set of design workshops with students with Fred Deakin. We were based out of the Design Museum but ran a number of the days fully online for flexibility and to help the students tune into online modes of collaboration. One of the exercises involved a kind of round-robin where an idea was passed round the group for comment and development. The key was that everyone would go in turn – but how to decide the order of speakers in the Zoom-like platform we were using?

My suggestion was to draw a very simple diagram of a table (just a square) and place each of the participants’ names around it for each group. We then shared this simple ‘map’ into the non-space of the platform and asked the groups to go clockwise around the table. This was an easy way to establish the order the discussion should go in, but I also noticed that there was suddenly a greater sense of togetherness and place. You could imagine who you were sat next to or opposite, and while this didn’t change the functionality of the technology it did change the psychology of it. It didn’t take much to help people imagine themselves into a shared location.

Spatial collaboration

Whether it’s the location of topic areas in the library, the paragraphs in an essay, the bullet points in our notes or the way we arrange files on our computers, understanding (how we arrange and develop our thoughts) has a spatial element to it. Even the phrase ‘making a connection’ is inherently spatial. In a similar manner our social relations are spatial, from where we sit in a meeting to if we spend most of our time in the kitchen at parties. Both the social and the conceptual involve us creating schema and maps to navigate by.

Recently I was developing a set of ‘practice-genres’ to help define what areas of practice any given digital technology could help to facilitate. For example, the VLE/LMS might fall under the ‘organizational’ genre, while Zoom/Teams/Skype would be under ‘real-time teaching/collaboration’. One of the more interesting genres was ‘real-time spatial collaboration’ in which I placed Mural, Miro and Padlet (Although there are plenty of other examples that would fit the genre).

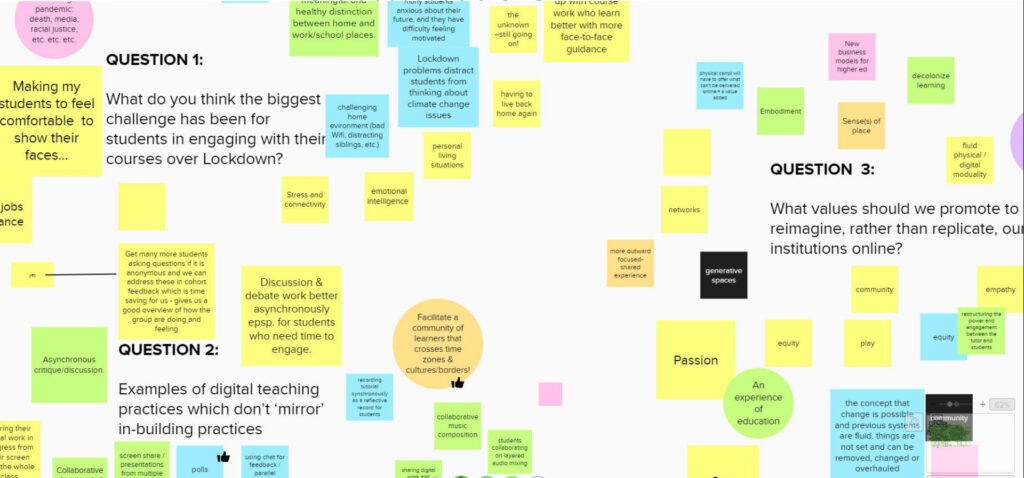

Spatial collaboration is inherent when we are co-present in buildings but often lacking in the online environment. It is a form of collaboration which I’ve found the most rewarding during the pandemic, most notably during a session I ran at the Digitally Engaged Learning conference. In the session I asked everyone in a Zoom ‘room’ to join me in a Mural whiteboard. About 30 people appeared in the form of named cursors and answered three questions with digital sticky notes while we discussed via voice. I think only I had my camera on but nobody was looking at it as we were all concentrating on the Mural space. What we saw was a ‘collaborative swarm’ of cursors which was a little distracting at first but as the sticky notes appeared it suddenly felt like we were together, in the same place, working on the same thing. This is then not an attempt to recreate the physical, it is an imagined space and all the more powerful for that.

There was no uncanny valley here because there were no bodies present – the cursors and notes were enough to give a sense of where people were in a spatial-conceptual hybrid. We were building a map of thinking in a location where we felt co-present, embodied by our work, not by images of our bodies.

This hybrid mode, which maps both the thoughts and the location of individuals in a shared space generates a sense of co-presence which is more substantial and sustainable than a ‘sea of faces’ skeuomorphic presence. I believe that stepping away from our bodies in this manner is what is required for us to create the most rewarding and valuable forms of togetherness online.

*Gaming

It would be remiss for me not to mention what I believe to be the most successful form of online spatial collaboration which is multiplayer gaming. However, this is a complex area as a game will be geared around its own world, goals and challenges. It will not be designed to help get work done other than the work of the game-world itself. There is also the risk of the uncanny valley, here generated by attempts to render the ‘real’ in photorealistic CGI rather than by beaming in our webcam feeds into a grid. The results can be similar though, unless you are prepared to role-play. This is why games like Minecraft are so successful, they create an authentic sense of space and a dependable world with knowable rules and effects but, while it is aesthetically consistent, it is not attempting to recreate the ‘real’ in visual terms. This schematic aesthetic allows us to imagine ourselves into the space in a manner which more ‘real’ simulacra push us away from.

It doesn’t have to be ‘cutting edge’

As with my earlier example of the simple map of a table this approach doesn’t have to involve fancy platforms like Mural or game-worlds. Schematic presence comes in many forms. For example:

- Co-editing an online document when each person’s cursor/location in the document is visible.

- Creating a schematic of the ‘main’ and breakout rooms in a synchronous online session so that people can imagine moving between them spatially.

- Using the whiteboard to answer a question in Zoom/Teams etc

The principle of schematic presence also applies to non ‘real-time’ situations too. It is possible to create a schematic of how different platforms or locations fit together when working on a project or a course. This provides a useful map to help navigate what could otherwise be a totally conceptually disconnected scattering of spaces (or non-spaces). Through developing and iterating a map of this type a group can negotiate their way towards a shared understanding of the imagined space.

The key is to step away from the body as the primary instigator of presence and to generate schematic or topographic forms of location. Avoid trying to recreate the ‘real’ and instead concentrate on providing cues which help to spatialise thinking and identities.