Over a decade ago, I took a home brewed virtual ethnography approach to a project looking at communal and cooperative player behaviour in World of Warcraft. It appeared to me that the teamwork and sense of belonging in the game was exactly what we were trying to foster in online learning.

The method I used was to sit with a player as they gamed, asking the occasional question while I set-up screen recording software. I then left the hard-drive with them and asked them to record any moments that they thought were significant over a period of about a week. I picked up the recordings and made notes as I watched them. Then I went back to the player with specific questions about aspects of the play and the dynamics of the gaming community I needed interpreting. It worked well and led to my thinking on ‘Social Capital in the Pursuit of Slaying Dragons’.

( John K CC BY-NC-SA)

In the world and of the world

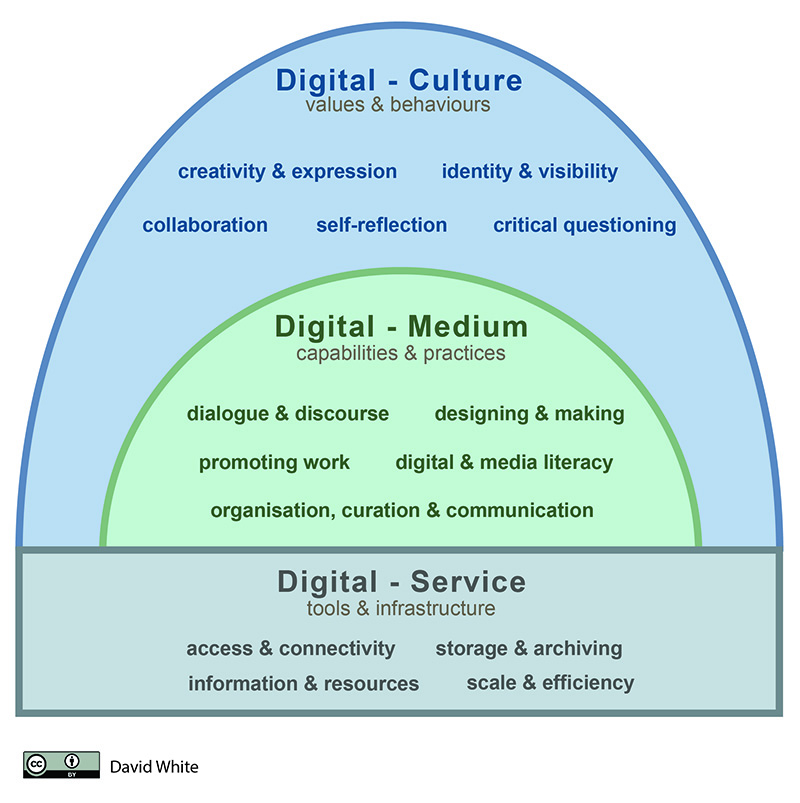

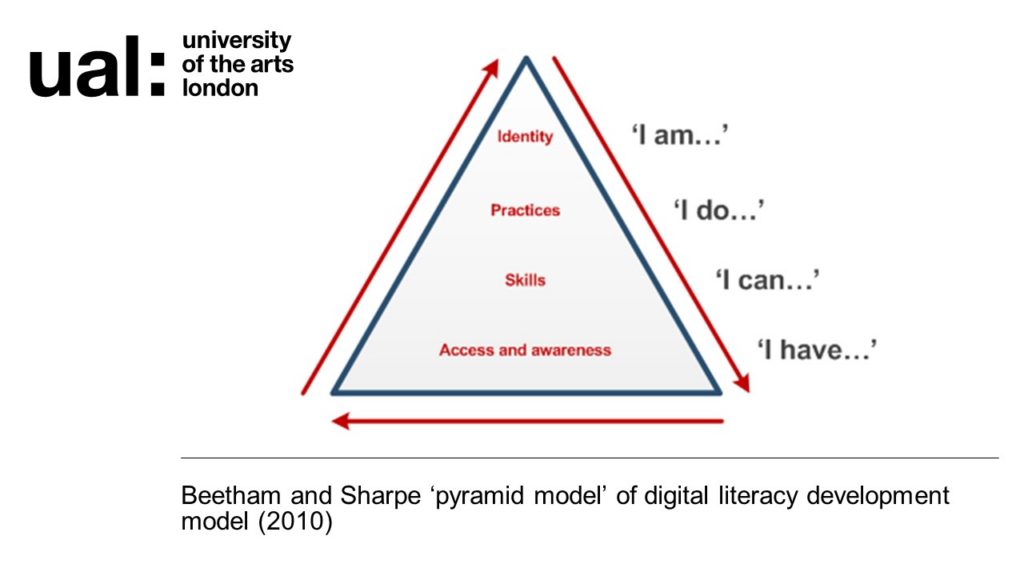

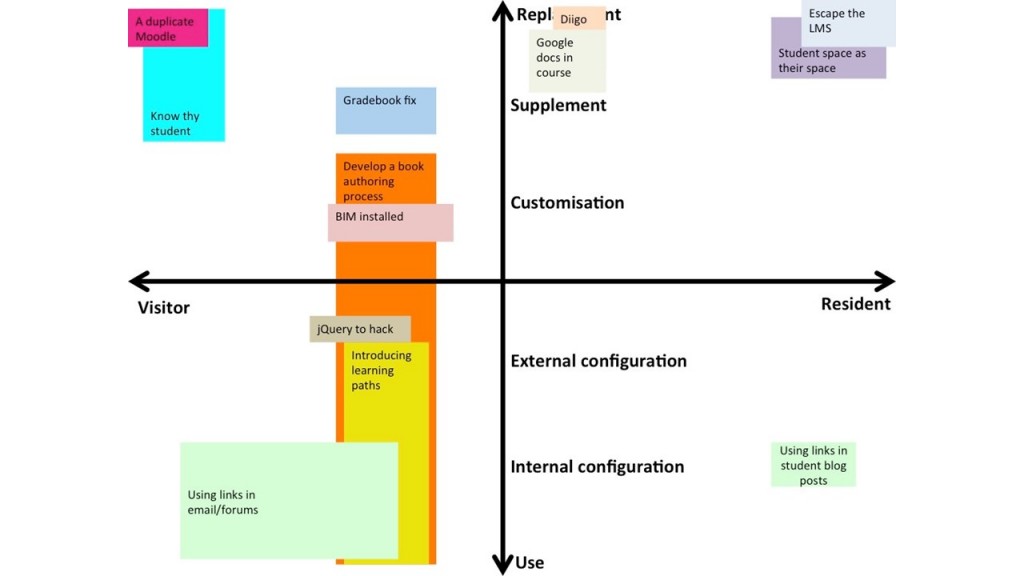

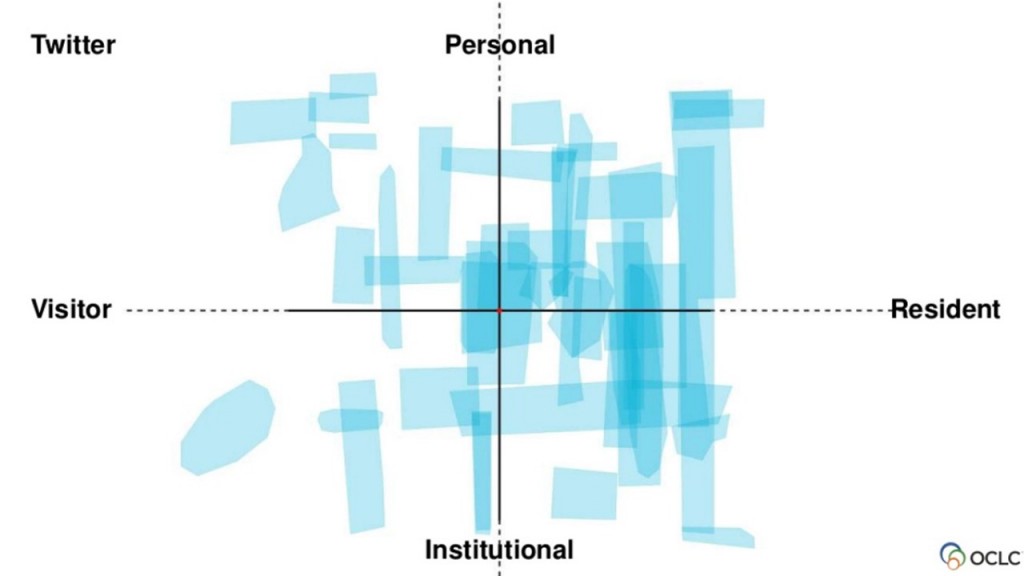

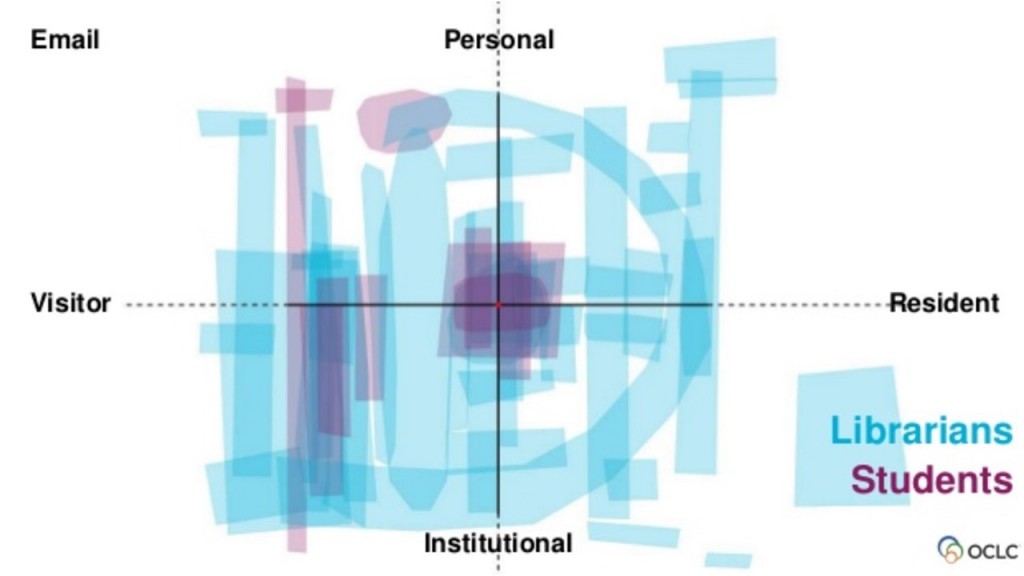

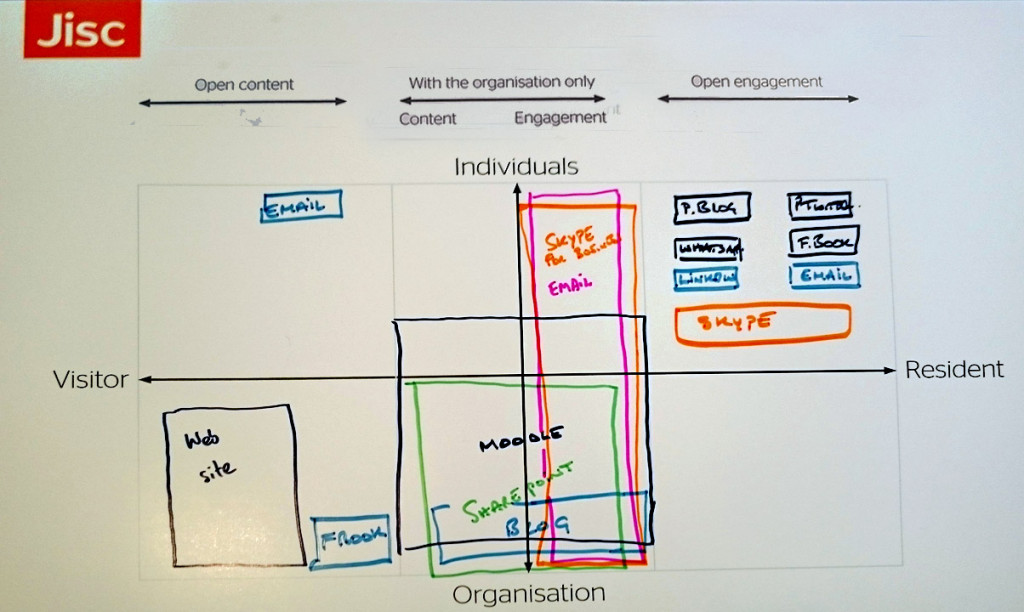

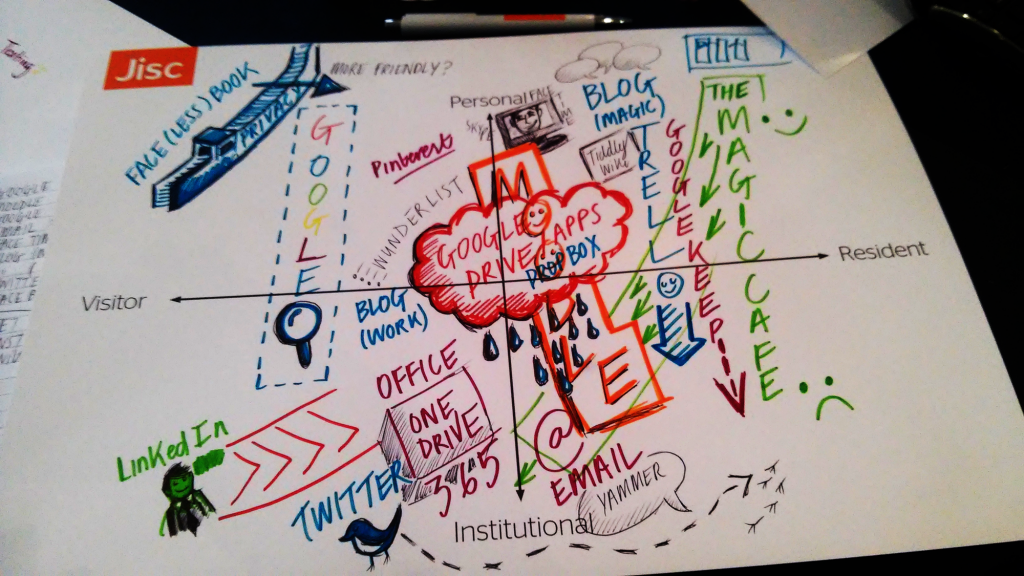

What was clear was that the players were extremely present in the game world, as embodied by their player avatars – they weren’t controlling a character from afar, they were within the world when they were gaming. The game was a space in which they were co-present, which is one of the reasons that an ethnographic approach worked. This principle influenced much of my subsequent work and I find it useful when considering the notion of digital fluency. In essence, you can’t understand the modes-of-engagement of a space by only learning it’s technical functionality as if it were a tool – you need to understand how it works as a social space. A simple example is Twitter – learning about ‘at’ replies, retweets and direct messages doesn’t tune you into the culture or discourse of the network of co-present individuals. You completely miss the role and value of Resident-mode platforms if you only consider how it works in abstracted, technical, terms.

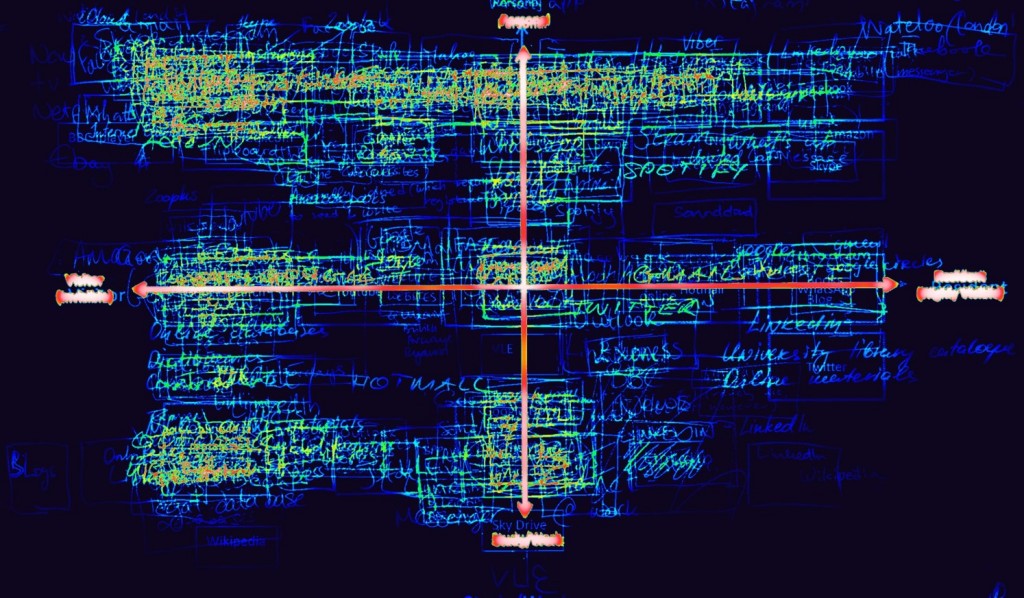

So when it comes to teaching about the potential role and value of Resident online spaces I tend to take a digital fieldwork approach which draws on this ethnographic thinking. There are usually decent guides on the basics of online platforms you can point people too so, beyond this, what becomes important is the fieldwork brief which provides a motivation to engage with the dialogue and the culture of the space. This is what I had in mind when I designed the digital fieldwork activities which we used as part of the Teaching Complexity seminar series.

Digital Fieldwork activities

The activities range from simply appearing in a Resident space (for those that have never operated in this mode) through to experimenting with an alternative identity or faking out a social media platform. The six activities come with a short video intro from me as explaining the context for the approach is extremely important. This is especially the case for the activities which involve experimenting with identity as it’s not about tricking anyone, so participants need to be sensitive in the way they present themselves and connect.

The identity based activities are inherently self-reflexive as they encourage participants to not be ‘themselves’ – this creates contrasts which can be reflected upon. In our daily engagement with Resident online spaces we will struggle to ‘see’ how the platform is influencing us because we are generally connected to like-minded, similar people and are therefore focused on the substance of those relationships rather than on the structure or culture of the environment.

This is similar to the anthropological principle that it’s difficult to see our own culture because we are normalised to it, which is why when we travel we gain insights through the contrast with other cultures. Taking on an alternative identity online is the equivalent of going ‘abroad’. The same Social Media platform is many different places depending on who you appear to be and how the platform encourages you to build your network based on your personal characteristics (age, gender, location, ethnicity, and anything else it can glean from your data)

My Instagram experience with an alt identity

A good example of this in the digital fieldwork was my own experience of the ‘Try on a New Identity’ activity. I started an Instagram account (having not had one before) as an alternative persona and began by following profiles/accounts suggested by the platform. The result was extremely informative. I gained an insight into the predominant aesthetic (in terms of fashion and ‘look’) of the platform and found just how much more sophisticated Social Media had become in shaping connections since I last ‘started from scratch’ in Twitter over a decade ago. Because I was an alternate persona it was extremely obvious why Instagram was throwing certain things at me based on my apparent age, location and gender.

It was now clear to me how the platform might cause anxiety through the pressure to conform to a very particular body image, mode-of-speech and lifestyle. It was also clear that various forms of authenticity were being performed which appeared to shift as accounts became more popular (the I’m-so-popular-I-can-now-reveal-the-real-me effect). Lastly, I was shocked that despite certain flags from the platform it was impossible to tell the difference between a person and a brand. I didn’t know when I was being sold something and, in some senses, everyone was selling ‘self’.

For me it was a distressing window into the convergence of self/product/brand which I often hear discussed but hadn’t seen so directly. The experience gave me a real insight into one of the potential reasons why our students can feel anxious about the online environment. Instagram implies that everyone can be famous but only by conforming to very particular ways-of-being (or performed ways-of-being). Obviously I had experienced a very limited and, in many ways, naive window into Instagram, which is what I had set out to do. There a many positive aspects to engaging with the platform which I didn’t experience because of the route I had taken.

Caution

To be clear (and in keeping with my own advice on the fieldwork) I was careful to only like posts and never commented or got into conversation. I didn’t gain access to anything that wasn’t already openly visible on the Web. I also only ran the account for a couple of weeks and it’s now mothballed. The activities are not designed to be used as research and as you can see I’ve been totally non specific even in this reflection. The persona I chose was not special, famous or someone anyone could have hoped to gain something from. I wouldn’t claim any persona is ‘neutral’ but I tried to be as boring as possible.

Reflections from participants

You can read some participants’ reflections on the digital fieldwork activities on the Teaching Complexity website. One of the most encouraging aspects of the approach for me was the depth of discussion generated by participants simply considering, but not doing, the activities. There was much discussion and reflection in the online sessions from people exploring why certain activities made them feel uncomfortable and the implications this might have for students who would be navigating similar choices. Ultimately, the activities are a useful prompt to generate thinking about how our identities are being used, and possibly abused, online and how this is now inextricable from the overall student experience.