A conversational seminar series exploring the future of creative art and design education in digital spaces.

Digital spaces and practices are evident in almost all creative and learning journeys. This is reflected in students’ experience of Higher Education and in the Creative Industries’ increasing emphasis on online collaboration.

However, fully online creative education remains difficult to imagine as it appears to contradict key characteristics inherent in ‘residential’ provision in various ways, for example:

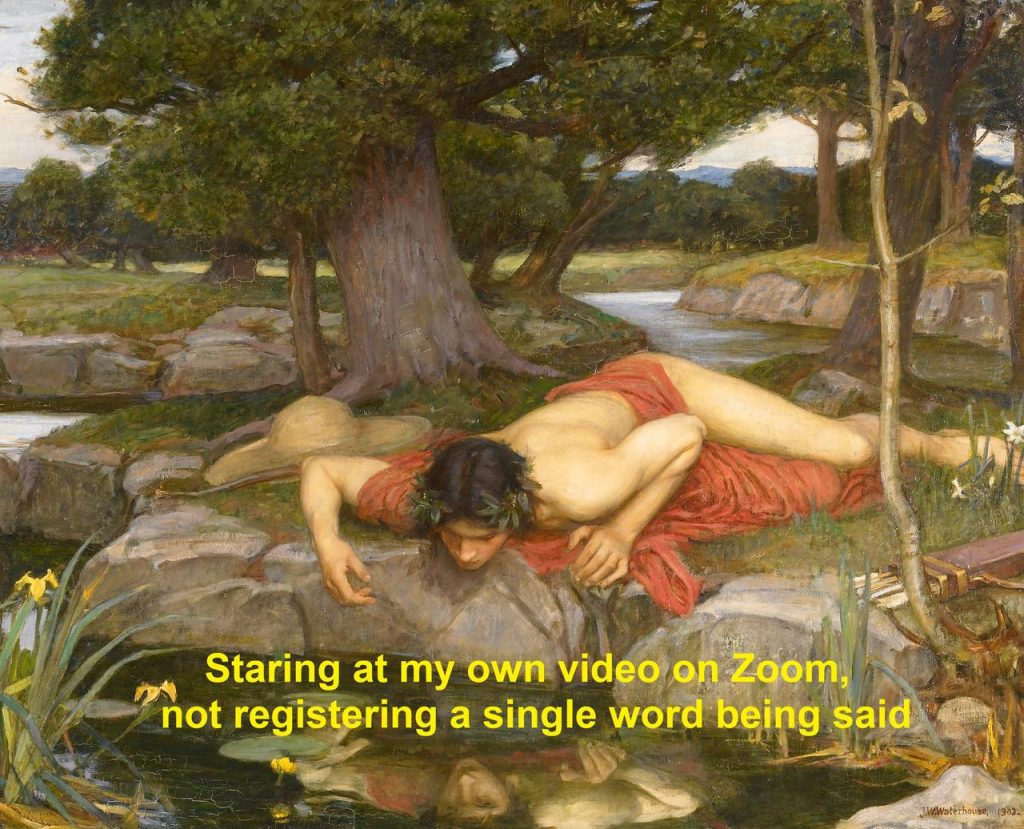

- The ‘desituating’ of material practices, embodiment and notions of co-presence.

- An assumed lack of ‘togetherness’ and group cohesion through increased flexibility of provision.

In conversation with experts this series will explore the challenges and opportunities for fully online and digital creative education, the implications for the identity of our subjects and institutions.

To what extent does online provision amplify and reflect current tensions around access, scale, and creativity? What aspects of subject tradition should be questioned in the attempt to be more inclusive and what should be protected?

Context and call

I’ve been working with Chris Rowell and Ruth Powell in the Teaching and Learning Exchange to put together a seminar series with a focus on fully online creative education. The format will be similar to Chris’ excellent ‘AI conversations’ from which he produced a digital book: ‘AI Conversations: Critical Discussions about AI, Art and Education’.

Each seminar will be a 30-minute informal interview, or conversation, with an expert on the relevant theme followed by 15 minutes of Q&A. They will take place on the 1st and 3rd Friday of each month, hopefully starting in May 2024. Below is a brief description of the series and a selection of draft themes.

If you are interested in being the ‘expert’ half of a conversation on one of the themes below, or if you’d like to suggest your own theme within the framing of the series, then let me know on david.white@arts.ac.uk. The questions for each conversation can be agreed in advance, with a focus on fully online but with space to go wider if relevant as almost all themes will have implications well beyond any single mode of ‘delivery’.

Suggested themes

Not all of these themes are my ideas, some came from Chris Rowell and Ruth Powell. I did draft them all, so they are written from my perspective. You might like the look of a theme but want to rework it so it comes from a slightly different perspective. Some of the themes are quite well thought through, while others are just the sketch of an idea. You might also notice that a similar theme has been expressed in more than one form.

Hopefully they give a sense of some of the ground we’d like to cover.

Desituated curriculum

What does it mean to teach creative subjects with little or no shared access to buildings?

Or

What are the implications of teaching and learning having no clear ‘situation’? Everyone involved is embodied in different locations, potentially with no geographical or spatial resonance?

The ‘virtual’ crit

The crit is central to Art School teaching, a practice with a heritage in Fine Art which carries through to many creative subjects and is commonly viewed as a signature pedagogy. Inherent in the crit dialogue in a communal situation. How does this play out online where a sense of togetherness is perhaps more ephemeral and the artefact under consideration will be digital or will have been translated into the digital.

What does an authentic crit look like in online spaces? What is gained and what is lost as we transpose a revered teaching practice into a new context?

Anti-oppressive online

Beyond notions of inclusion, we can ask what it means to be anti-oppressive online. What pedagogic practices “…legitimate students’ epistemologies, foster reflection and discussion, establish expectations of critical awareness, and democratize educator and student roles.”*

How does the principle of anti-oppression operate in digital spaces and places? How do we successfully navigate the ‘built-in’ power assumptions our online platforms and our own institutional cultures?

*Migueliz Valcarlos, M., Wolgemuth, J.R., Haraf, S. and Fisk, N., 2020. Anti-oppressive pedagogies in online learning: A critical review. Distance Education, 41(3), pp.345-360.

AI and creativity

Does AI make us more, or less, creative? How is It being incorporated into creative processes? Where is it redefining, or erasing, practices? Where has it morphed esteemed practices into ‘skills’? What are the implications for creative subjects and identities if we consider AI as a technology of cultural production?

AI literacy, AI use

What literacies and uses are emerging in creative education. Exploring day-to-day practices and implications (staff and students). What aspects of AI literacy should we be focusing on as creative educators?

Translate to engage?

Instantaneous text-based language translation was an early, widely available, use of Large Language Model AIs. Now the same process can work in real time with text or audio.

In UK Higher Education there is anecdotal evidence that some students who have English as an additional language habitually translate teaching into their primary language to engage.

Is this a technology of decolonisation and inclusion or a twisty example of cultural homogenisation by Silicon Valley? What does this mean in terms of belonging and the intercultural in an education system which is resolutely ‘taught and assessed in English*’?

Can we imagine the 100% translated course?

*If we are speaking from a UK perspective.

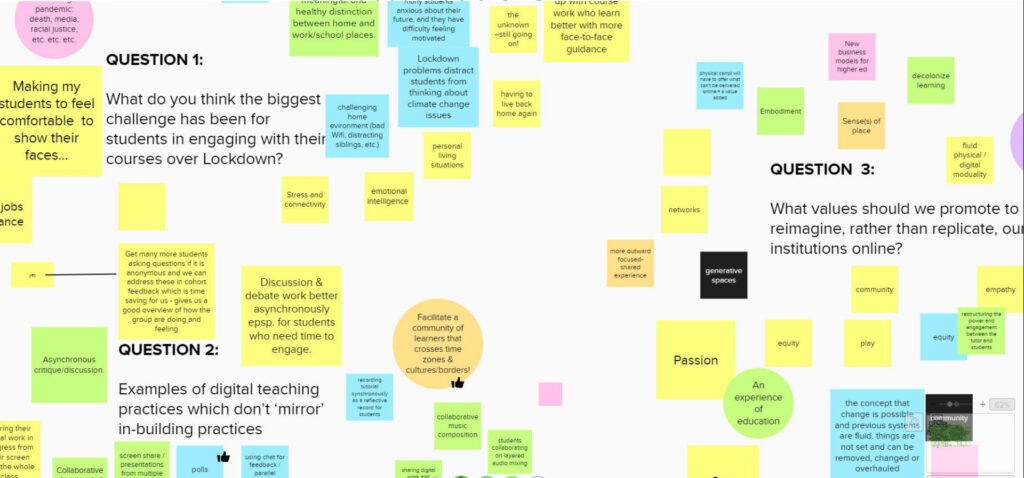

Assessment, feedback and tech

To what extent has a move into the digital environment modified our assessment and feedback practices? Are we replicating or reimagining?

For fully online provision, what does it mean to be assessing a digital simulacrum of material work? Is a shift in emphasis from ‘realisation’ to ‘process’ in assessment a radical turn or simply a reflection of ‘good practice’?

Dispersed materiality

How do we reconceptualise ‘Studio’ as a concept (a shared space, a set of practices and dispositions) when making is dispersed, distributed across time and geography?

A lack of object-ivity?

How does/should object based learning work in the immaterial digital environment?

The tantalising prospect of digital ‘immersion’ – placemaking with VR/XR.

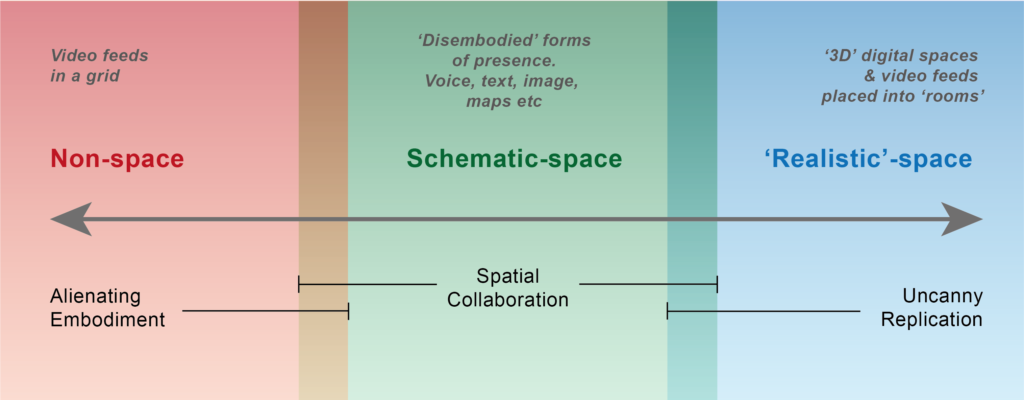

One response to the immaterial nature of the digital environment is to simulate the ‘real’. To what extent is the use of VR/XR a legitimate method of ‘uploading’ art and design practices into the digital? Does spatial tech draw us together by providing new places of co-presence or does it exclude and isolate?

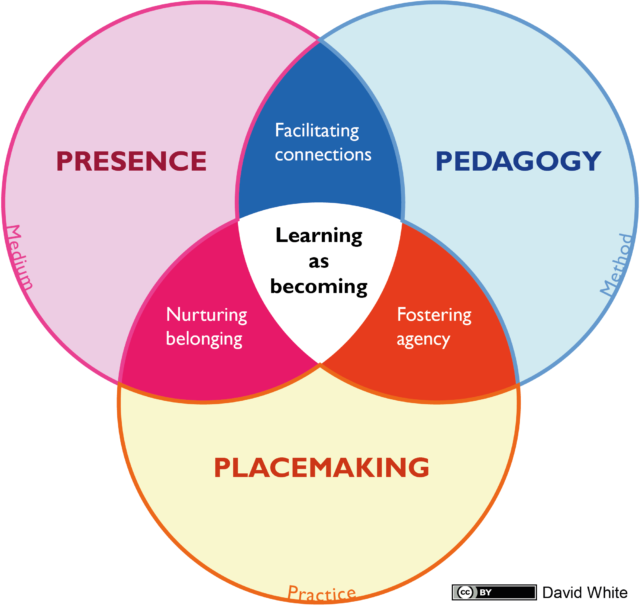

Being and belonging

Creative arts demand a pedagogy of becoming – being through doing. Given the flexible and dispersed nature of online education how do we ensure we are creating the conditions for this?

Digital mess

The spaces of online education are commonly designed in the context of a corporate philosophy of efficiency and task management – they are spaces as imagined by Silicon Valley. Add to this the inorganic nature of computing and the creative possibilities inherent in the massy and the unpredictable become attenuated. To what extent can we co-opt these environments towards mess and chaos-within-bounds which so often inspires the creative process?

Digital and climate emergency

To what extent is moving creative education online an effective response to climate emergency. What are the factors in designing a low carbon digital curriculum? Are we simply dispersing our responsibilities across a myriad of physical locations or does a reduction in travel immediately make fully online education the most climate-ethical mode of education available?

Lumpy stuff and digital

The plastic arts, getting your hands dirty, materiality etc. Where do we handle the ‘lumpy stuff’ in online creative education? What happens when the tactile, the visceral, cannot be sensed or shared through physical co-presence. Is it possible to meaningfully ‘make’ when dispersed across many localities. Additionally, how might we transpose the lumpy work into the digital without losing its essence. What does it mean when all work ends up as a digital image?

Creativity in corporate spaces: i.e., “Microsoft is the location of your college”

Similar to the Digital Mess theme but with more focus on the implications of relinquishing our spaces to Silicon Valley. There is something here about the corporate ownership of communal spaces and notions of the ‘safe space’ online.

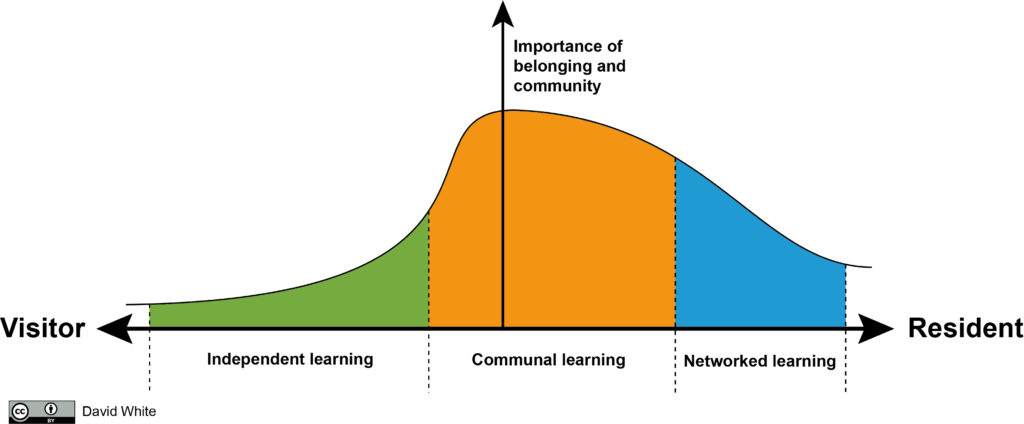

Flexibility vs communality

Fully online education is a pragmatic option for people will full lives. It can be offered flexibly to account for the ebb and flow of work, caring responsibilities and ‘life happening’. However, this flexibility erodes the notion of the cohort and the shared experience of a group going on a journey which is ingrained in creative education. To what extent is flexibility the enemy of communality and belonging? What are the possible design responses which create the potential for communality without always mandating that students ‘build their lives around the course’?

Immaterial making

A Fine Art educator once commented that during an online Fine Art MA the students central practice became the art of making PDFs.

How do we ensure that the screen does not dominate in making subjects? What might be effective and enjoyable methods of sharing and communicating the material via the immaterial?

Access vs supervision

Creative arts education is centred on the development of individual and collective creative practice. This lends itself to a ‘pedagogy of supervision’ which supports individualised dialogue and questioning. While this is likely to be meaningful and inspiring for the few who can access it as a form of education it is inherently expensive, demanding significant amounts of academic/teaching time.

To what extent does a financially viable and accessible approach to online education negate a supervision approach? Is it possible that accessible online education unpicks the very nature of creative subjects, or perhaps demands that they be reimagined?

Structure vs reflection

All creative processes require moments of reflection, space to think, space to forget and then reconnect etc. In contract, good practice in online education tends towards structure, and the granular quantification of attention and focus. Given this, how might we design creative online education which scaffolds but does not suffocate, which provides space-to-think but not an absence of purpose? What does it mean when the most intense moments of learning and creativity are often those times that cannot be measured or entirely predicted?