This week I was on a panel hosted at the House of Lords to discuss the launch of the Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning report. The research is from the Higher Education Commission, written by Alyson Hwang.

The report’s research heritage has its roots in scrutiny of online learning during Covid lockdowns but things have come a long way since then. The Office for Students commissioned a review of blended learning, led by Professor Susan Orr which was published in October 2022 which forms a basis for this new research. The key finding from that 2022 work was that teaching quality is not relative to mode:

“The review panel took the view that the balance of face-to-face, online and blended delivery is not the key determinate of teaching quality. The examples of high quality teaching that were identified in this review would be viewed as high quality across on campus and online modes of delivery. This also applies to examples of poor teaching quality.”

Blended learning review, Report of the OfS-appointed Blended Learning Review Panel, October 2022

It seemed that everything moving online during Covid had caused a culture shock and certain voices in Westminster decided that learning online couldn’t possibly as good as learning in buildings. Plus, some students were making the case that they were paying the same fees for an inferior experience.

This was more about university as a cultural-rite-of-passage than as an educational journey, but it largely got framed as being about ‘learning’. A valid question here would be ‘which students are we taking about?’ and ‘on what basis?’. See this recent piece from the Guardian by Roise Anfilogoff, who points our that for many students university became significantly more accessible during lockdowns.

The new report

The Commission found that blended learning has the transformative potential to widen participation and access to higher education for all, improve equality of opportunities, and enhance learning outcomes.

Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning Report, pg 20

The Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning report builds on the Review of Blended Learning, adding information from evidence sessions, interviews and written submissions to support a rangy set of recommendations. The case studies root the research in current, successful, practice.

It’s notable in how positive it is about blended learning and while there are many caveats, all the case studies and stats are upbeat. I’m sure this is an effect of asking institutions to share stories, rather than a taking a detective work approach. However, given the Covid heritage of this line of reporting it’s interesting that nowhere is blended learning portrayed as a bolt-on or fundamentally ‘not as good as’ being in physical rooms. I sense we are heading towards post, post-Covid times in quite a helpful way.

The report covers a lot of ground, ranging from the need for leadership to the state of the ed tech market. All-in-all it’s a useful body of work to support institutional strategy and to make the case for investing in Digital Education in the broadest sense.

Year zero

Much of what is covered and recommended are things which those of us in Digital Education have spent many years arguing for. In this sense the report is largely describing the current start-of-play rather than presenting possible futures. Covid is taken as a kind of year-zero for blended learning which doesn’t change the value of what is being said but always feels strange for those of us who have been working in the space since the 90s.

The following recommendations in the report are ‘classics’ and well underway in many places:

- The need for senior leadership roles that own and promote blended learning.

- The need for more staff development and time to be made available in workload planning for this.

- The need to incorporate digital literacy/capability into all curriculum to equip students for the workplace (and, I’d add, life…)

- The need for commercial ed tech development and procurement to be more agile, and possibly collective (Open Source doesn’t get much of a look-in).

Certainly the Association for Learning Technology community have been extremely active in these areas and are well placed to contribute to any cross-sector work.

Asynch

The aspects of the report which open up the most interesting areas for me are around how we might develop more nuanced models of ‘blended’ as a practice and how ‘Quality’ might then be defined. The report proposes the following model:

| Time, pace and timing | Synchronous and Asynchronous |

| Space | Place and Platform |

| Materials | Tools, facilities, learning media and other resources (digital, print-based or material) |

| Groups | Roles and relationships (teacher-led and peer-learning, varieties of learning groups) |

This is a useful and useable set of categories and it’s heartening to see the concepts of space and place in there. The report goes onto suggest how quality might be overseen, or measured, in recomendation12:

The Office for Students should establish a single, coherent approach for assessing the quality of online and blended learning as the designated quality body, ensuring that metrics do not impose additional bureaucratic burdens on the HE sector.

Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning Report, pg 6

This is complex and problematic because, as the report mentions, all provision is blended to a degree and so any coherent approach for assessing the quality of online and blended learning will actually be assessing all provision. Moreover, if we believe that this is about the quality of teaching (and design of provision) rather than the mode then why would we want to focus on mode? Not to mention that we already have a significant burden of regulation which the report alludes to as potentially distracting.

The HE sector is facing a significant challenge due to the regulatory landscape’s lack of consistency and stability. This diverts resources from developing teaching practices, investing in digital infrastructure, and improving students’ experiences.

Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning Report, pg 33

Teaching beyond mode

This all comes back to a knotty point that, in regulatory terms, we don’t have a workable definition of teaching that operates super to mode and can be applied across face-to-face and digital. For example, when you sift through the OfS Conditions of Registration the examples given which relate to teaching have their roots in face-to-face, ‘synchronous’ practices. There are refences to the need to use ‘current’ pedagogies in digital delivery but these are not described. As in this ‘possible cause for concern’:

The pedagogy of a course is not representative of current thinking and practices. For example, a course delivered wholly or in part online that does not use pedagogy appropriate to digital delivery, would likely be of concern.

OfS Conditions: B1: ‘Academic Quality’, B1.3

High Quality Academic Experience, Cause for concern 332H (b.)

It’s reasonable pedagogic specifics are not described given that ‘current thinking’ is a moving target. However, the side effect of this is that teaching is frequently refenced but never described, which means we fall back into a ‘contact hours’, teaching is the live stuff, way of thinking. Ultimately, most of our measures of teaching quality are proxies via student experience. There is plenty of merit in that but it contributes to the problem that our shared understanding of what teaching is (and what it isn’t) is always implied, or assumed, and never made explicit.

The asynchronous unicorn

Although the regulatory body provided some practical guiding principles, the metrics for assessing the quality of blended provision could be clarified to guarantee quality education rather than penalise innovative practices.

Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning Report, pg 32

This is important because until asynchronous forms of teaching are actually understood as teaching we won’t be able to describe the value of blended, or fully online, learning. Until ‘non-live’ pedagogies are mapped into our understanding of quality we won’t, as a sector, be able to see our own provision clearly.

The effect being that the way in which the digital can support truly student-centred flexible provision will not be acknowledged and much progress in access and inclusion will remain ‘invisible’ to quality frameworks. This extends to the way we design contracts, manage workloads, increase student numbers and widen access. The latter being a key hope attached to the hypothetical flexibility of online and blended provision, especially for those already in work:

Contributors to the inquiry voiced how student needs and demands are changing in line with the economy – more than ever, students are benefitting from flexible, personalised, and accessible delivery of their courses.

Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning Report, pg 4

As mentioned, the key here is to describe and communicate-the-value-of ‘non-live’ teaching in a mode agnostic manner. This isn’t about Digital, it’s about teaching and flexibility– it just so happens that Digital allows us to undertake many forms of ‘non-live’ teaching (whereas non-digital forms of asynchronous largely rely on a postal service).

(aside) What do we think of when we think of teaching?

I’d like to undertake a research project where we ask a cross section of staff and students to describe what they understand by the term ‘teaching’. I suspect views will vary wildly and worry that many of them will be quite narrow.

What can we take from the Digitally Enhanced Blended Learning report?

There is plenty of useful stuff here and I’m sure it will be quoted in many strategies and budget asks. It’s a useful step forward, not least of which because it reflects the reality of the majority of the sector and not some kind of Oxbridge cultural romanticism, projected out from, bricks and mortar.

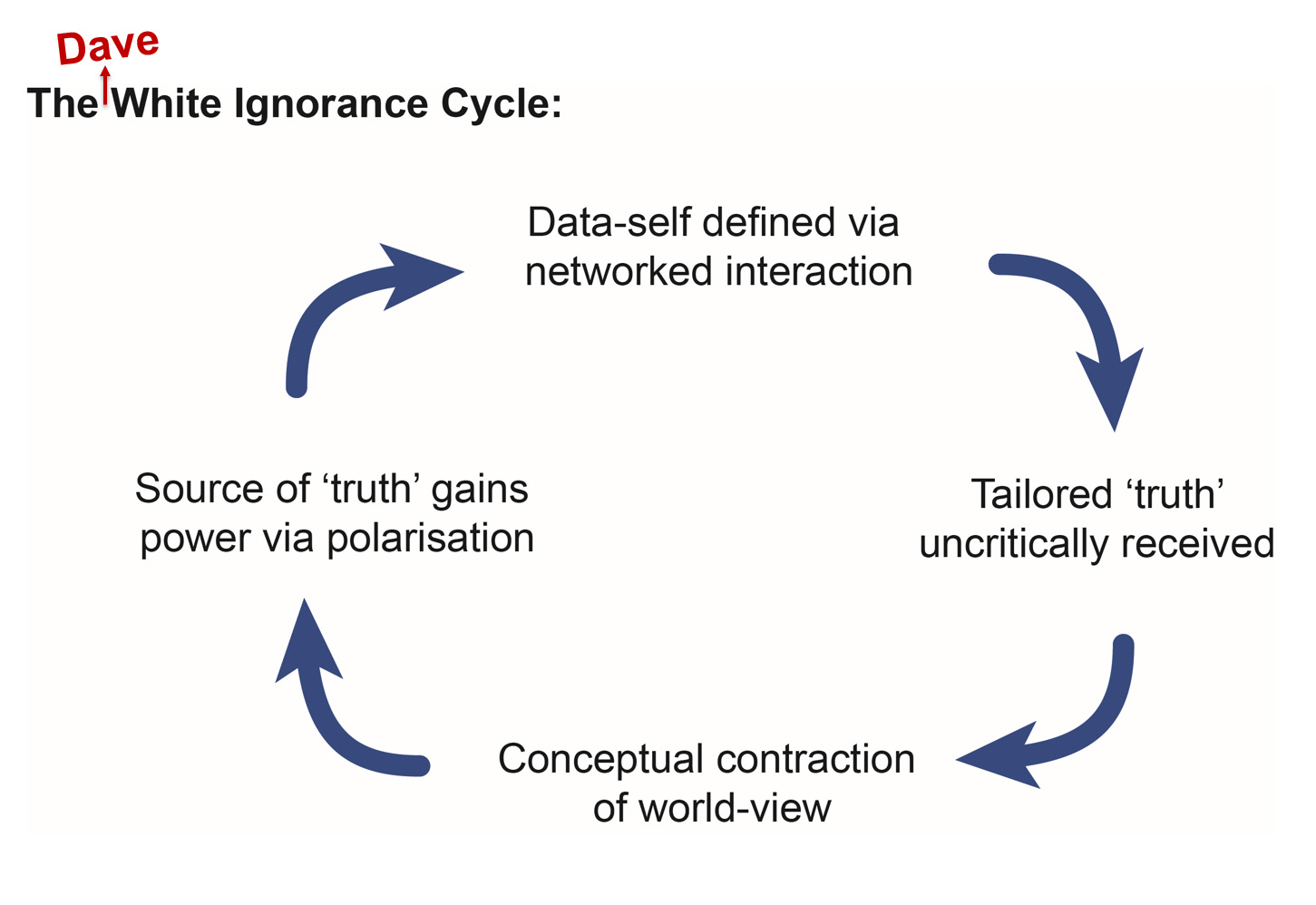

Overall, I’d ask where the investment and capacity might come from during nervous times and I’m wary of a narrative which is based on the White Heat of Technology as it’s never really about the tech, it’s about the business model. Certainly, in a sector where we are generating an ever growing staff precariat, introducing technology to make things ‘more efficient’ is likely to contribute to instability. I say this not entirely from a Marxist perspective but because I believe that meaningful teaching will always involve confident, highly capable, professionals.

To give the report it’s due, at no point does it suggest that we should do everything with AI or something along those lines, it’s driving more of an access than efficiency agenda, but it’s focus on mode, rather than the practice of teaching could lead people the wrong way. My hope is that the constructive and measured character of this report will provide a basis for us to develop more sophisticated models of practice and quality which are not tied to mode and therefore don’t segregate digital.