Pre, during or post pandemic – however you look at it, online and blended learning have come in for some serious critique. This has evolved since 2020 from blunt assertions that universities were ‘shut’ during lockdowns, to more considered reviews of ‘blended learning’ such as the one currently being undertaken by Professor Susan Orr (at one time my boss at UAL) for the OfS.

A definition of ‘normal’?

The language around this is interesting as terms like ‘returning to normality’, ‘quality’ and ‘experience’ are used in a manner which implies there is an ideal model waiting to be sculpted from the substance of recent years. Underlying this is an assumption of a homogenous student community which is engaged in a residential undergraduate, or postgraduate, course. The ‘typical’ student will be between 18 and 25, have moved to be close (within a walk or a bike ride) to campus/college and will be on a course which takes between one and four years to complete. i.e. The university experience most people who now run universities had (including me).

I wonder what percentage of the Higher Education student population this represents now? I’m sure it’s a declining percentage, because whatever we decide about online and blended learning we are going to be doing more, not less, of it, and this invites in new/different students.

The tug-o-war

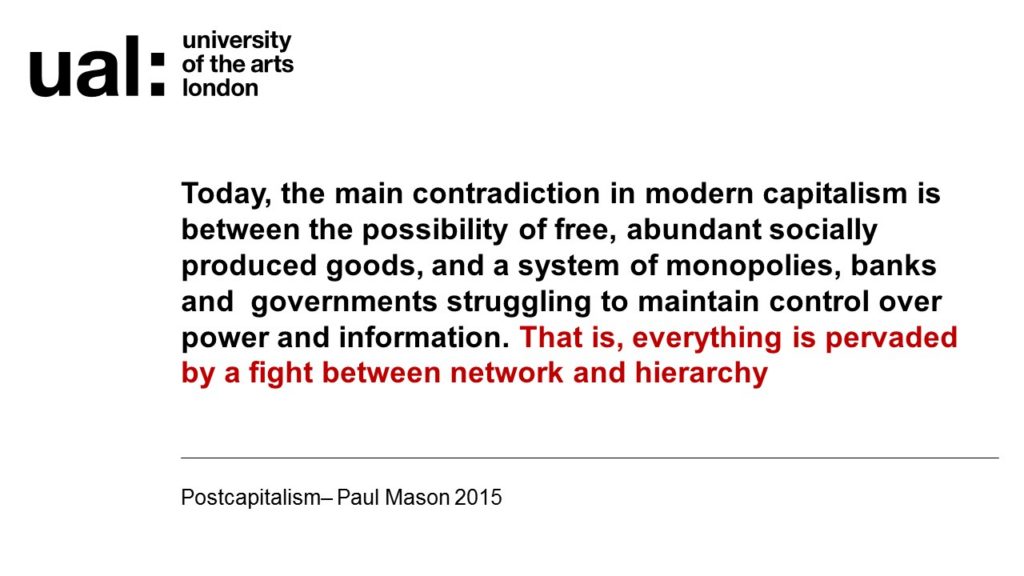

Reflecting on this I realised that debates about key terms such as ‘normality’, ‘quality’ and ‘experience’ are often argued from differing, but rarely explicitly stated, positions. The Venn diagram here maps these as ‘Culture’ and ‘Education’, with ‘Sustainability’ being a key theme emerging from the current tensions.

Culture

Type ‘university’ into Google image search and you will see manicured lawns, sophisticated architecture and smiling young folk with mortarboards. This is our cultural conception of Higher Education, a rite-of-passage largely modelled on Oxbridge or Russell Group institutions. For many, ‘doing university’ is an important journey of identity formation and independence which goes way beyond any scholarly activities. I certainly don’t degenerate this aspect of Higher Education, but I do worry that it is still the yardstick we use to assess more diverse modes-of-education than this rite-of-passage concept of ‘university’ can contain.

This is a yardstick largely fashioned by those who experienced a narrow, privileged, route through Higher Education and see it as needing protection from being ‘watered down’. The concern is always for ‘quality of education’, but when scrutinised it can often be shown to be a defence of education-as-cultural-filter.

University understood as a cultural rite-of-passage is a powerful notion. It is frequently the motivation behind student demands for forms of provision such as in-building teaching which is, in turn, linked to perceptions of value-for-money. We love to know that ‘proper’ university is occurring somewhere, even if we are not always convinced of its ability to help us learn.

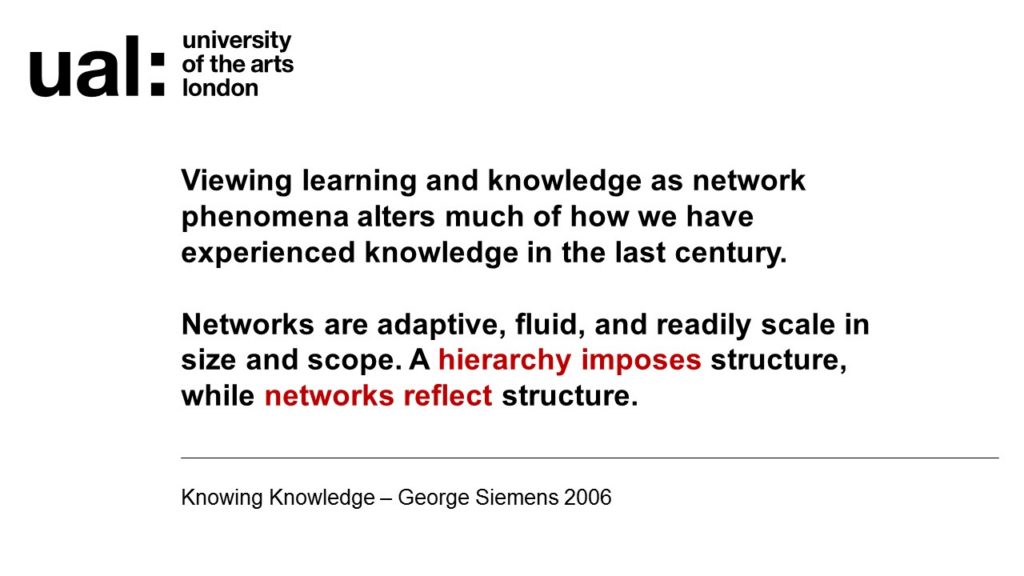

Education

Clearly, any student experiencing university as a rite-of-passage will be learning plenty about what ‘success’ looks like. They will also, we hope, be learning a specific subject or practice in some form. Making progress through a subject, or developing a practice, is linked with notions of the ‘effectiveness’ of the mode. With online or blended modes and there is plenty of evidence that students can be successful in pedagogic/scholarly terms but a lingering suspicion that this is still not an authentic experience.

The confusion starts when focusing on ‘quality’ (as in ‘students were disappointed with the quality of education they received’), which mixes ideas of ‘rite-of-passage’ and ‘education’ in various ratios. Complex terms such as ‘belonging’, ‘community’ and ‘experience’ come into play. Terms which can become so twisty that it’s tempting to reach for the rite-of-passage yardstick to beat them into shape.

My point is not that these less quantifiable ideas are not important, it is that they are more, or less, important depending on who you are and what you are trying to achieve. Lawns and mortarboards framed as the only, or the root, rite-of-passage makes huge, and culturally romanticised, assumptions about who our students are, what they want, and what means they have to access the ‘education’ of university.

Both the ‘culture’ and the ‘education’ concept of university are valid in different ways, our institutions will always be a shifting mix of both territories. The danger is that by not understanding which side we are arguing from, the discourse stagnates or remains no more than politicised rhetoric. In the meantime, blended and online modes will continue to grow but without a reasonable way of assessing them which accounts for the diversity of incoming students’ circumstances, privilege and aspirations.

Sustainability

Given that, by any measure, we will be accepting more students and offering a broader mix of modes, the key question shifts from ‘authenticity’ and ‘effectiveness’ to sustainability. Whatever we believe to be the most elegant model of university, it has to be facilitated and run in a way which doesn’t exhaust staff or students.

This requires clarity in describing the value of the modes we are offering, as opposed to a description of how those modes may, or may not, conform to an imagined ideal. It also requires new definitions of roles which are still designed around lawns and mortarboards in ways which, more often than not, don’t map to the day-to-day demands of the work.

Over the pandemic this problem has been amplified by an increased use of digital technology as the primary location of our institutions. The management of work-load as a side effect of the physical limits of in-building activity fell away and we discovered we were not adept at managing our time when work can be undertaken 24/7. This was also compounded by a sincere desire to support students and colleagues in a time of crisis.

There is a task ahead to rethink our relationship with work in an environment where technology has outstripped our abilities to set boundaries. Being honest about the conditions of the system we are operating within is the first step towards developing a truly inclusive and sustainable environment for everyone involved.