Part of my thinking around the Web and education is as follows:

- The Web is brilliant at feeding us the information we need to get things done in a highly relevant manner.

- We still tacitly design pedagogy as if this wasn’t the case on the basis that ‘good quality’ information must in-of-itself be difficult to obtain and that by implication online information ‘can’t be trusted’

- This approach is founded in our cultural adherence to the form rather than the substance of information. (for example our veneration of the concept of a ‘book’ or notions of what it means to be an ‘expert’)

(both 2 and 3 are a hangover from a period in time when we held information behind locked doors) - The new challenge for education, driven by point 1, is how to encourage learners to ‘think’ in an era where answers are easy to come by (on the basis that the challenge of finding information used to, in-of-itself, encourage critical thinking and reflection)

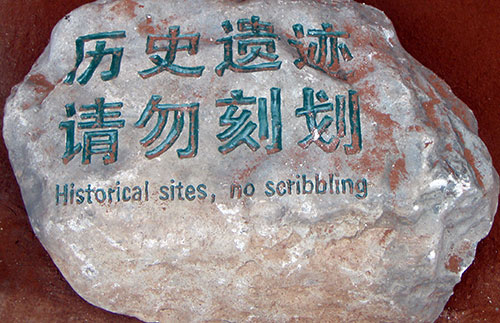

Let’s imagine a scenario where most of the key ‘answers’ to curriculum are easily found online. (This will increasingly be the case on a relevance driven Web as the answer to any regularly asked question will rise to the top of the search return). If we construct our pedagogies around the search for answers in this manner then the efficiency of the Web will place students in a role similar to that of the person inside Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought experiment.

In the thought experiment Searle, who does not understand Chinese, is locked in a room with a set of rules in English which “enable [him] to correlate one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols” – the latter symbols being the Chinese language. Given this, people can post questions in Chinese into the room and Searle can translate them successfully, posting back answers without having any knowledge of Chinese himself. The people receiving these answers falsely believe there is someone in the room who understands Chinese.

This has been used to make a case against the notion of Artificial Intelligence by claiming that Searle’s activity in the room doesn’t require him to understand Chinese and that by implication he is not thinking or reflecting on the Chinese language but simply following a set of rules.

In my version of the scenario Searle is our student, the Web is the set of rules and the Chinese language is any question posed by our pedagogy to which an answer can be found online with a simple search. Ironically this frames the student as ‘unthinking’ technology and the Web as the embodiment of intelligence via the algorithms, or ‘rules’, it employs to feed answers back via the student.

We have compounded this problem in the light of the Web by losing our confidence in teaching how to think and retrenching to defending our authority as the font of knowledge. Education should not be about establishing the worthiness of certain forms of knowledge, especially if we ascribe to Feyerabend’s rejection of universal method, it should be dialectic process, interrogating, synthesising and pushing forward our understanding.

[Side Note: There are numerous examples of sectors/businesses moving into a protectionist mode just before being overtaken by the digital. Good examples include newspapers and imho traditional academic journals. Universities embody high levels of cultural capital and are more diversified than many people realise. Nevertheless, they risk becoming overly anachronistic if they don’t equip graduates with significantly more than what can be gained by owning a smartphone. Side, Side, Note: Clearly the ‘beauty’ of higher tier universities is their ability to make being anachronistic the very basis of their cultural capital]

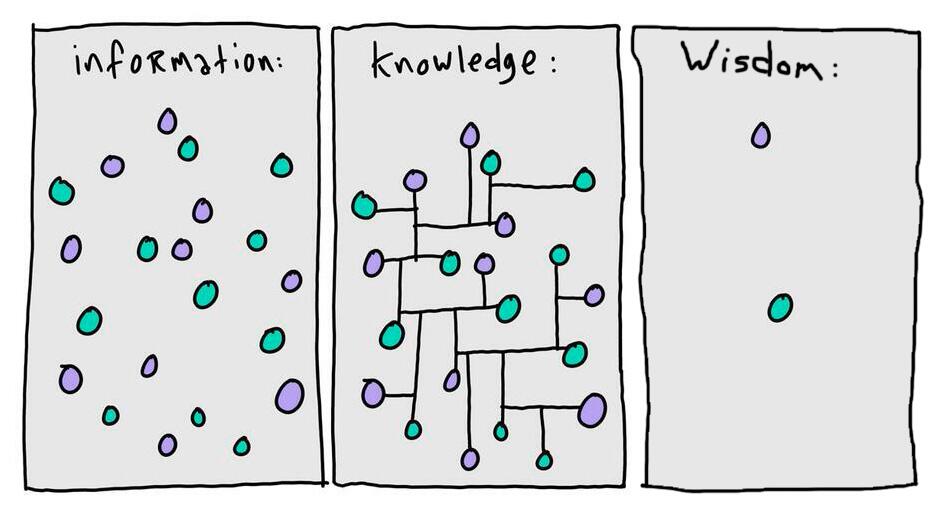

Once we realised that anyone can publish online (the most radical aspect of the Web) our first reaction as educational institutions was to focus on evaluating sources because they hadn’t been pre-vetted by the library or written by one of us. My contention is (and my research shows) that the Web works very well in terms of information quality and relevance which in turn re-emphasises the importance of teaching how to use and connect knowledge not simply how to decide if a piece of information is to be trusted. For me this is as the very heart of what a higher education should be.

The challenge for us then is in finding ways to encourage learners to critically reflect on the manner in which they engage with, and use, the Web epistemologically rather than only concentrating on the critical evaluation of isolated chunks of information. In some senses this is simply a move in emphasis from ‘digital’ literacy to a more generalised form of literacy.

Getting this approach across to students requires clarity though because it usually cuts against their perception, and experience of, education as an exercise in discovering ‘answers’ (especially if they have recently left school). Just warding students off the Web or implying that online sources are fine as long as they are the same as things you might find in the library (the usual marker for credibility) is missing the point. The Web should be encouraging us to move to the higher rungs in Bloom’s taxonomy all the sooner or our pedagogy risks students in the Chinese Room with Google Search.