Through the Visitors and Residents work I am frequently involved in discussions around identity, especially in relation to online spaces. Often discussions that start with technology, move onto practice and then morph into questions of identity: How does my professional identity relate to my personal identity? How does my online identity relate to my offline identity? To what extent am I performing different identities? Which of these many dimensions is the most authentic or is that authenticity contextual? etc.

These types of questions are brought to the surface by our relationship with the digital because it provides a new mirror to hold up to ourselves. Going online in Resident modes is not unlike travel in this sense, we question who we are as we encounter new spaces, forms of communication, modes of meaning and ways of being.

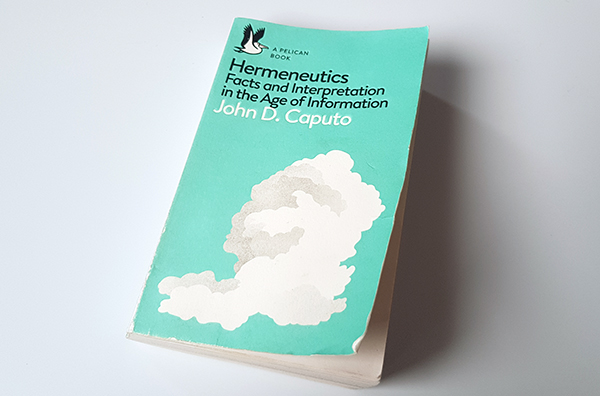

I’ve always been happy to facilitate these discussions but I’ve not taken a position on identity apart from making it clear that using the term ‘real’ (as in ‘real-life’ vs ‘digital’) is spectacularly unhelpful as generally when people use term ‘real’ casually they mean ‘something I’ve become normalized to’. My sensitivity to hard-edged distinctions around real/digital or authentic/fake is indicative of my belief in the importance of interpretation. This is why when a colleague gave me a book entitled “Hermeneutics, Facts and Interpretation in the Age of Information” by John D. Caputo I drank it in.

Hermeneutics, Facts and Interpretation in the Age of Information – John D. Caputo

Chapter 7 on ‘The Call of Justice and the Short Arm of the Law’ which explores a lecture given by Derrida in 1989 at the Cardozo Law School inspired me the most. It didn’t fire me up about the law or justice but rather the character of Derrida’s approach to Deconstruction. Where Derrida spoke of law and justice I could read identity and self. The more I mused on this the more helpful I’ve found it in describing a model of identity which is based on becoming-through-interpretation. So, to this end, I will inelegantly summarise a wafer of Derridean thinking and then extend this into a new, identity-based, context.

The most important aspect of justice as described by Derrida, via Caputo, is that it is impossible and does not exist. Justice is unreachable but it yet it calls us to move towards it (Caputo likens this to a spectre or ghost), whereas the law is constructed and has force (and structures and physical components – courts, police, prisons etc).

We hope to make just laws but will never attain a perfectly just legal system. Any attempts to respond to the call of justice require that we interpret law in each given situation or context. A law applied without interpretation is extremely likely to lead to an unjust outcome. Our attempts to be just exist between the deconstruction (or interpretation) of the law and the undeconstructable call of justice.

We need the impossible to create a distance within which can deconstruct or interpret. (I recommend you read the chapter – I can’t do it justice here…)

It struck me that the notion of the ‘self’ was much like Derrida’s positioning of justice. It calls to us like a ghost or a dream but it is contested and slips through our fingers as we attempt to define or describe it. Attempts to define self and being is the fuel of philosophy – as alluring as it is confounding. Perhaps this is because, like justice, self is simply impossible and its power is in this undeconstructablity – a horizon we might travel towards but never reach. A journey we might take knowing we will never arrive.

To extend this, identity becomes akin to Derrida’s depiction of the law, something which is constructed and has force within the world. If we run with this line of thinking then it is through interpretation of identity that we respond to the call of self. We can never fully arrive at our-selves but we can deconstruct our identities through interpretation, towards the self . I consider this process of continual deconstruction and reaching through interpretation, usually via dialogue, to be ‘becoming’.

As with justice and the law what becomes crucial within this conception of self and identity is the willingness to deconstruct or interpet. Damaging essentialization based on shoring-up (sure-ing up?) well worn binaries such as real/virtual, authentic/fake falls away as the ‘work’ of identity becomes interpretation, questioning and negotiation.

This is in stark contrast to the view that we already somehow contain our true self, a self we must express through our identity. On this view we are constantly attempting to project our self into the world as an authentic identity. There is a kind of violence to this in which we fight external factors (institutions, individuals, society, culture etc) that might repress our true self. In some cases, where individualism has reached its zenith, we are told that it is us who is repressing our own true self and are invited to unlock our real selves, usually via purchasing something. Certainly there is plenty of money being made via products that claim to help us to express, or be, the ‘real’ us on this model.

Our digital environment also supports this model as within Social Media negotiation of identity through interpretive presence is commonly replaced by acknowledgement of essence. Collecting followers and likes authenticates and quantifies our existence without the need for deconstruction. We will not move any closer to the horizon of self if our sense of identity is based on validation through acknowledgement rather than engaging in dialogue and deconstruction. This then leads to a creeping alienation in which we constantly seek acknowledgement to secure our identity but make no progress toward self and feel increasingly ephemeral.

Similarly we cannot reach towards self if the only people we connect with provide a homophilic mirror of our current identity state – this is a comforting form of identity stasis which, in conjunction with the need for essential acknowledgment, breeds polarisation. We inevitably bolster our ‘authentic’, internalised self through the constant re-establishment of what we are not, in a process of unbecoming.

In my view then, agency is not the power to enforce our identity on the world but the conditions and desire that support us in deconstructing our identity towards self. This form of becoming is challenging, requires us to be vulnerable and is fraught with risk. Given this, the conditions become crucial and it is much less risky for those in a structurally privileged position, such as myself, to engage in identity deconstruction. I have many institutional safe-spaces I can retreat to if I ‘overreach’ towards self.

In this regard there is much work to be done to move our institutions to places in which a diversity of identities can be negotiated. I understand why certain environments can only be engaged with through a forceful projection of self and identity, especially where individuals feel misunderstood, repressed or ignored. Those are the mono-culture environments which pretend to invite negotiation but which are merely looking for acceptance and assimilation.

Those environments create conditions which breed polarisation and amplify individualism in a manner which extends, rather than interprets, difference – our identities become fixed and our horizons become walls we build. In astronomy there are no walls, we can see to the edges of the universe and glimpse our shared beginning. Through deconstruction of identity we travel towards a shared and connected horizon of self.