(This post was written before the main wave of interest/anxiety around AI/Large Language Models hit. As such, it’s delightfully non specific and an attempt to outline implications in principle. For me, this is summed-up as follows:

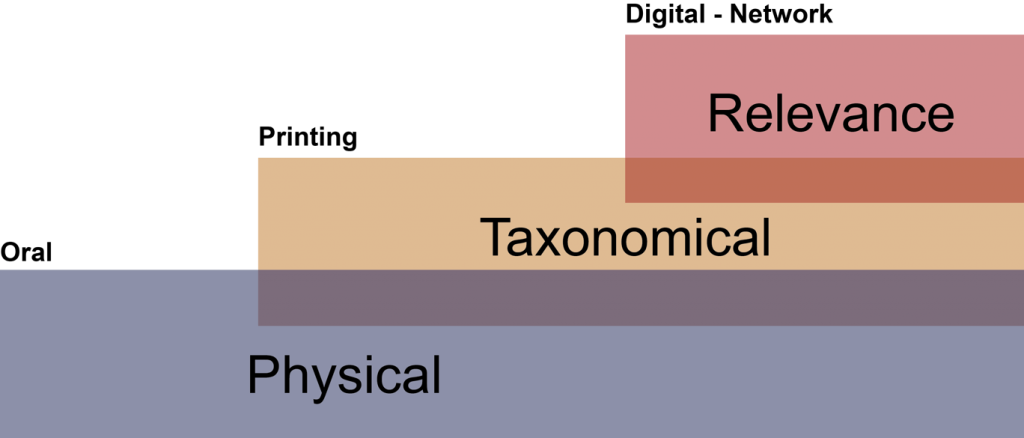

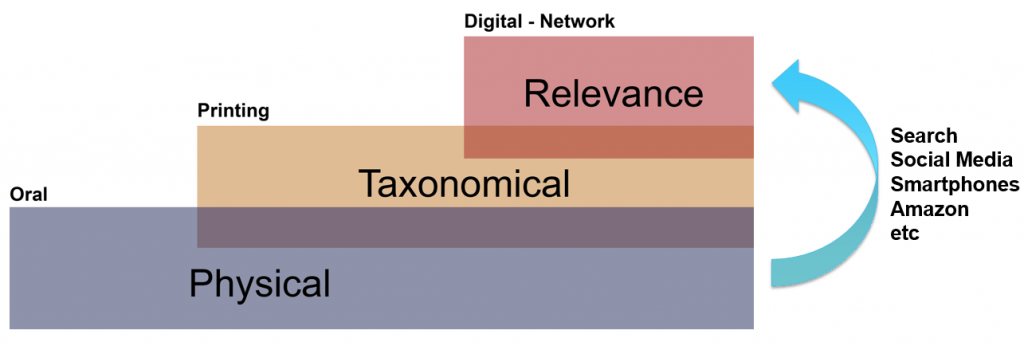

- Efficient access to abundant information (the Web) reduced the value of ‘remembering information’ as a skill.

- AI reduces the value of synthesis as a skill.

In some ways, technology is climbing up Bloom’s Taxonomy and pushing more of the learning process in the pointy bit of the triangle. Although, interestingly, it does skip some layers which could be a problem. Jumping from knowledge to synthesis and circumnavigating comprehension, application and analysis might prove dangerous. (not that I think we should always run through those things in strict order).

Anyway… below is what was my first run at some of this thinking)

A developer friend of mine recently told me a simple coding task they set when interviewing new staff was successfully answered by a chat bot. My response was, “Chat bots can Google, so I’m not sure what the problem is?”. In the days following my trite response I found myself coming back to the topic and realised that the chat bot ‘problem’ is part of a long history of falsely imagining ‘learning’ to be a fixed concept we are more or less distanced from by technology.

In 2014 I gave a keynote at the Wikipedia conference entitled, “Now that Wikipedia has done all our homework, what’s left to teach?”. This was intended to be a playful way of highlighting that the ‘problem’ was not with Wikipedia but with an education system which placed too much value on answers and not questions. Wikipedia was ‘too good, too available and too accurate’ for a system which was built on the principle that information is difficult to access and recall.

Looking back, the Wikipedia ‘problem’ seems like the quaint precursor to the lively AI-will-kill/save-education discourse. (all tech debates decend into the kill/save dichotomy, so it’s better to step back from this and ask why this comes about.)

Good / Bad – *yawn*.

Firstly, any institution or system which claims that technology becoming ‘good’ at something is the central problem won’t last long in its current form. Within Capitalist Realism, you simply never win this argument (and yes we could go to the barricades but I’m writing in the context of where we are now). Secondly, withholding technology to force people to ‘learn’, incorrectly assumes that the notion of learning is fixed. Let’s be honest, telling school kids to not use Wikipedia was never going to wash, especially as schools tried this line at around the time they stopped giving out textbooks on the (never to be said out loud) hope that the kids all had access to the internet.

Saying AI is bad (or good) is a super dull discussion. Admitting it exists and that we will use it for anything that makes our lives a bit easier is a much more interesting starting point. (side note: when I use the term AI, I really mean ‘elegant computer code that does things we think are useful or entertaining’). A brief history of humanity has to include: “We will always use all available tech for good and bad and this process is continually redefining what it means to have power, have skills, be intelligent and be creative.” These values and how they operate as currencies is always on the move and always has been.

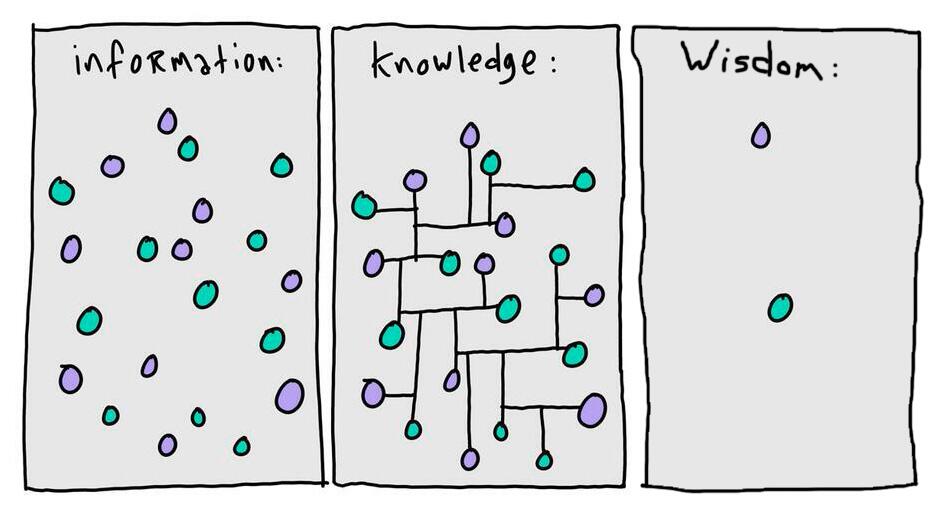

Is ‘being right’ now wrong?

What my developer friend’s chat bot couldn’t do was reason out, or tell the story of, how it had arrived at its answer. This is how we frame ‘learning’ at the University of the Arts London, we don’t assess the end product we assess the narrative of how the student travelled towards the end product. The narrative is the learning, the artefact (often a creative output at UAL) is the output from that learning. The end ‘product’ is symbolic of the learning rather than an embodiment of it, it needs a narrative wrapped around make meaning out of the process.

The photography(tech)-drove-art-to-become-more-conceptual argument is a useful touchstone here. If we imagine a near future where most, traditional, assessments of learning can be undertaken successfully by code then our approach to education has to become more about narrative and reasoning than about ‘being right’ or ‘reflecting a correct image of the world back at ourselves’.

We are feeling our humanity squeezed by tech that can mirror what we, historically, defined as human. This is not a fight with tech but an opportunity to redefine and reimagine what we value. I’m hopeful that this will allow previously marginalised voices and identities to become heard.

I’d argue that ‘being right’ is this century’s outdated skill – this is a good thing.

Just as purely figurative Fine Art lost a bunch of its value as photography gained ground, being right will lose its status relative to being-able-to-think within our networked-tech suffused environment. In many ways, current political and identity polarization is an effect of the rise of networked technologies, both in social (the internet) and neural network (AI) terms. It’s a grasping for the comfort of ‘being right’ in response to a painful, and unsettling, shifting away from the certainty of that very rightness.

Save and adapt

Back in edu-land: A good essay is a narrative of reasoning, so it does or should, operate as an embodiment of being-able-to-think. Sadly, we have fed so many essays into the network that technology can now reflect a performance of this learning back at us. I have no sympathy for educational institutions who have a naïve understanding of data and also claim that tech which endangers its business model should be shut down. We can’t complain about tech when we use the very same tech to increase revenue. We also can’t de-tech without damaging access and inclusion.

Let’s not to fall into academic navel-gazing on the what-is-learning/what-is-the-academy questions though. Instead let’s focus on how we adapt our lumbering institutions to shifting tech-driven redefinitions of value, while also calling our unethical practices of all kinds. I’m not an accelerationist, I believe that we can adapt while not erasing historical forms of value. Universities are ideally placed to ‘protect’ that which might be destroyed by the headrush of technology but they must not be defined by that impulse.