In Art and Design the shared endeavour of learning is usually understood as an ontological process, a process of ‘becoming’.

“The outcome of every learning experience is that it is incorporated into our identities: through our learning we are creating our biographies. We are continually becoming…”

Learning to be a Person in Society, Peter Jarvis, 2009

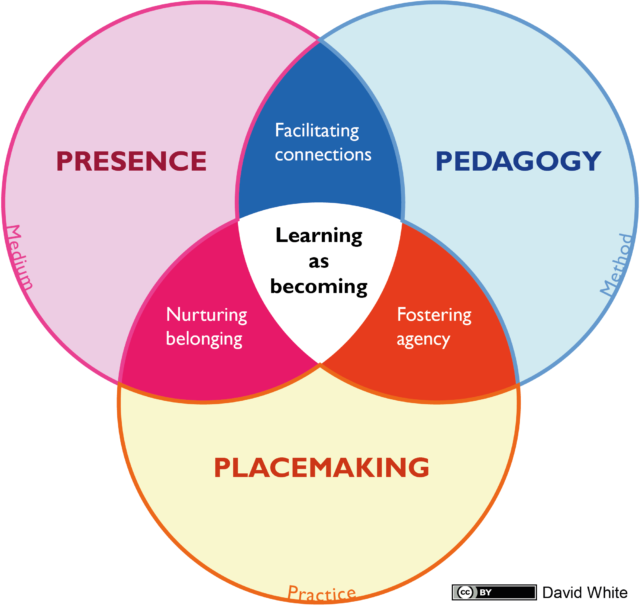

I would argue that this is the case for all education. If our students leave as exactly the same people they were when they entered, we have failed them. Given this, and building on the importance of presence and place, I propose this model of learning-as-becoming which can be used to holistically reimagine our institutions at a time of great flux.

The learning-as-becoming model

Part 1: Pedagogy as placemaking

Last year we took the University of the Arts London online in about three weeks and have been fully online, or heavily blended, ever since. Our teaching, technical and support staff have did an amazing job adapting working practices and redesigning courses so that our students had the best chance of learning and becoming during a global crisis.

There has been a generosity within most of the feedback from staff and students, an acknowledgement that this has been a long-running emergency. Putting aside discussions about fees, our students appreciate the massive effort teaching staff have been putting in and everyone is aware of the struggles involved in both teaching and learning under difficult, and highly varied, circumstances.

Beyond the immediate health and wellbeing concerns I would say that the most challenging aspect of the last 14 months has been a loss of place. Our buildings are a focal point for belonging, presence and community. They are a physical metonymy, a powerful symbol, of the idea of the university itself. Being denied access to our buildings was such a powerful loss of place it shrouded the fact that the work of the university continued online.

The digital non-place

We immediately, and understandably, attempted to recreate a sense of presence and place in the digital environment via our webcams. Many of us have now moved on in our approaches because we quickly found that the ‘mirroring’ of our physical environment in this manner was tiring and sparked an ongoing ethical debate around private space.

Ultimately, the problem was that we thought our Zoom/Teams/Collaborate sessions would give us back a sense of place because, like our buildings, there were people ‘in them’. However, picking up on an idea from anthropologist Marc Augé I would say that these types of digital platforms are ‘non-places’:

“The concept of non-place is opposed, according to Augé, to the notion of “anthropological place”. The place offers people a space that empowers their identity, where they can meet other people with whom they share social references. The non-places, on the contrary, are not meeting spaces and do not build common references to a group. Finally, a non-place is a place we do not live in, in which the individual remains anonymous and lonely.”

Marc Augé, Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, Le Seuil, 1992, Verso. – quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-place

The notion of non-place encouraged me to think about the process of placemaking and how this related to presence. Last year I wrote about the importance of presence, suggesting that we should focus on “Presence, not ‘Contact Hours’” when teaching online. Alongside this, the presence-based Community of Inquiry model started to appear in many discussions on how to move from ‘emergency remote teaching’ to something richer and more sustainable.

It struck me that any form of ‘presence’ needs a location to occur within – presence, by its very nature, requires place. This was the missing piece in my thinking and something we perhaps don’t consider directly when we have access to our buildings, because we take their place-ness for granted.

The symbiosis of presence and place

Our buildings are suffused with cultural and social histories. They are full of artifacts and objects that are coated in the presence of people who passed through before us. Even the leftover coffee cups and the arrangement of the furniture speaks of the presence of others.

Our institutional buildings are more than spaces, more than somewhere to keep the rain off, they are places, full of people and echoes of people expressed through objects and architecture. In contrast, most of our digital spaces are non-places. They are transient, they have no shared geography and, if we think of Zoom/Teams/Collaborate type platforms, we leave little behind to be discovered by others. We are not ‘Resident’ in any form – nobody lives there and we don’t work there.

Crucially, what makes a space, or non-place, into a place is social and intellectual presence. As discussed in previous posts, this presence can be realised, or expressed, in many forms (not just via the webcam). The semi-permanence of text, images, videos, digital post-its and the clutter of artefacts in platforms like Padlet, Miro and MURAL give agency to participants (assuming everyone is allowed to contribute) and build presence and place, especially because they have an inherent spatiality.

There is a complex interplay between the salience of our presence and the extent to which a sense of place is felt. Place and presence have a symbiotic relationship, they build on each other. However, in our transient-and-disembodied-by-default digital platforms we must deliberately set-out to set this symbiosis in motion.

Shared endeavour, leading with pedagogy

In both online and in-building contexts presence and place are catalysed by our pedagogy. That is, by the way we design and facilitate connections and collectively negotiate the shared endeavour of learning. The challenge we have been facing is that in the digital we start with a non-place, whereas our physical buildings have a place-ness we can build on before we even enter.

The emphasis in the model is on a pedagogic approach which first-and-foremost facilitates connections and forms of interaction, creating social, intellectual and creative presence. Through this, the locations of our institutions, especially the digital spaces, become places within which our students have agency. This then increases belonging and supports learning-as-becoming. This is pedagogy as placemaking through the medium of presence.

Part 2: The need to go beyond a model of delivery.

There is a certain pressure at an institutional level to develop models which respond to what we have experienced during the pandemic, reasserting the importance of our buildings and incorporating convenient online modes.There is a mix of motivations behind the development of these models:

- Responding to predicted shifts in student expectations, especially in regard to flexibility and cost-of-study.

- Managing the expectations of teaching staff in the context of students’ desire to return to buildings.

- Exploring the possibility of expanding student numbers and/or to connecting with new communities of students, when the limitations of physical space are mitigated by digital modes.

These models tend to draw on our in-building modes (lecture, tutorial, seminar, workshop, access to support and resources) and then discuss which of these modes are best suited to being ‘delivered’ online. The model then turns to what might be an acceptable ratio, or ‘blend’, of online to in-building delivery.

Practices have changed

This is a useful piece of thinking up to a point, but it falls into the trap of perpetuating the well worn approaches defined by the affordances of our buildings rather than exploring or supporting the more flexible and fluid possibilities in the online environment. This also attenuates our ability to reimagine the use of our physical spaces, which continue to be framed as resources that can be used more efficiently rather than differently. In essence, these are new models of delivery and not new models of practice.

However, I would argue that our practices have changed, as has our understanding of what it means to successfully work, teach and learn. In a recent post James Purnell, our Vice Chancellor and President, explores how we might prototype the future of work. I hope we can also prototype the future of education in a similarly open manner.

Yes, we could take a ‘fill in the gaps’ approach and continue to pit the digital and physical against each other – but that simply uses a mix of locations-of-delivery to perpetuate models of practice which have been outdated by a global emergency. The ‘fill in the gaps’ approach is also not capable of ‘seeing’ the new modes-of-engagement which have developed during the pandemic, modes which don’t neatly fit our classic delivery formats.

This is why I have developed the learning-as-becoming model which is focused on reframing practice and paves the way for models of delivery which can incorporate pedagogic approaches that do more than mirror that which went before.