Over the pandemic there has been much discussion of the need for community and belonging as part of the education experience. The emphasis in these discussions is that online didn’t/doesn’t ’do’ community very well. However, it’s more accurate to say that that sudden shifts from residential provision to online caused by a pandemic are not ideal for sustaining community.

Residential assumptions

As we develop, or expand, our fully online provision it’s important not to fall into the trap of designing with ‘residential assumptions’. What I mean by this is that we can assume that online students will want what our residential students demand (or what they missed when things moved online). Part of that is the need for community and belonging.

Inconvenience

Belonging is inconvenient, it requires commitment, accountability and time. Any anthropologist will tell you that there is no short-cut to belonging. Strong-bond relationships are formed because much time is spent together and the good times and the bad times are shared alike.

One of the key reasons that students can feel part of a community on residential courses is because they have made a huge commitment in time and effort just to turn-up. In traditional undergraduate terms this is likely to mean relocating the majority of their life to a new city for three years. It’s not just about the physical buildings it’s inherent in the format. In this sense, belonging is exclusive – available only to those who have the time to invest.

Just visiting

Once we move away from this traditional characterisation of students the need for belonging and community shifts. For example, as anyone who provides upskilling or updating courses knows, students in full-time work usually just want to ‘learn what they need’ and get on with their lives (lives which already involve community and belonging in other areas).

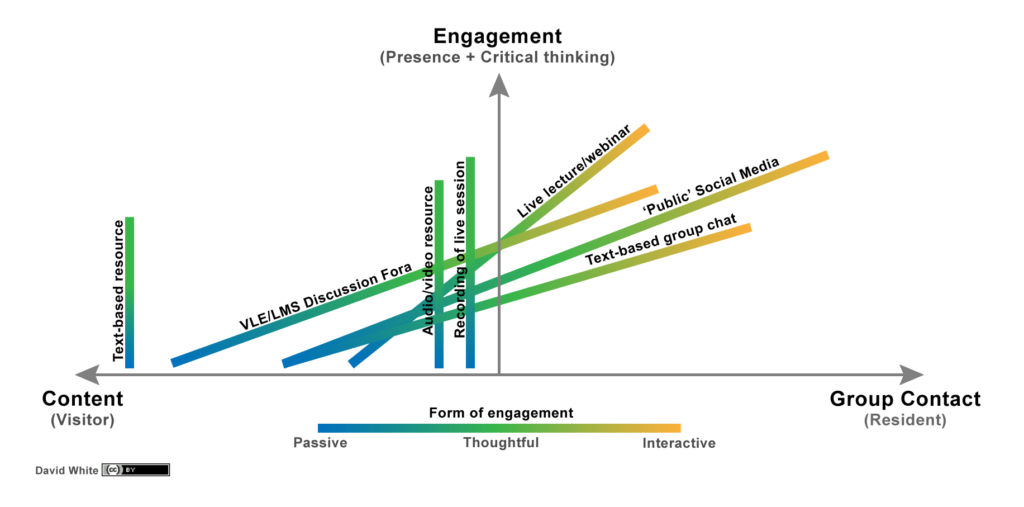

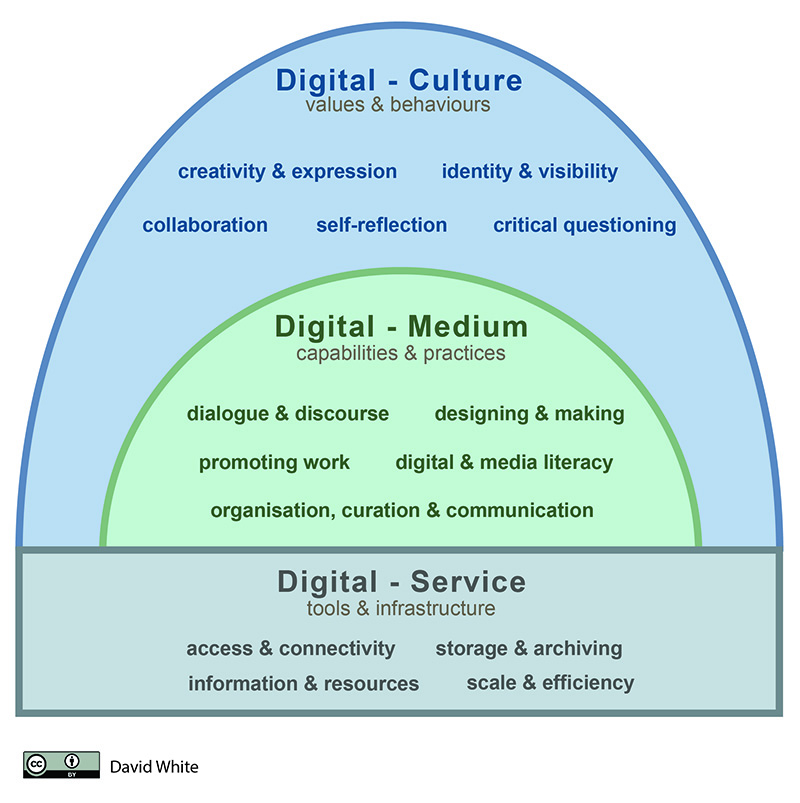

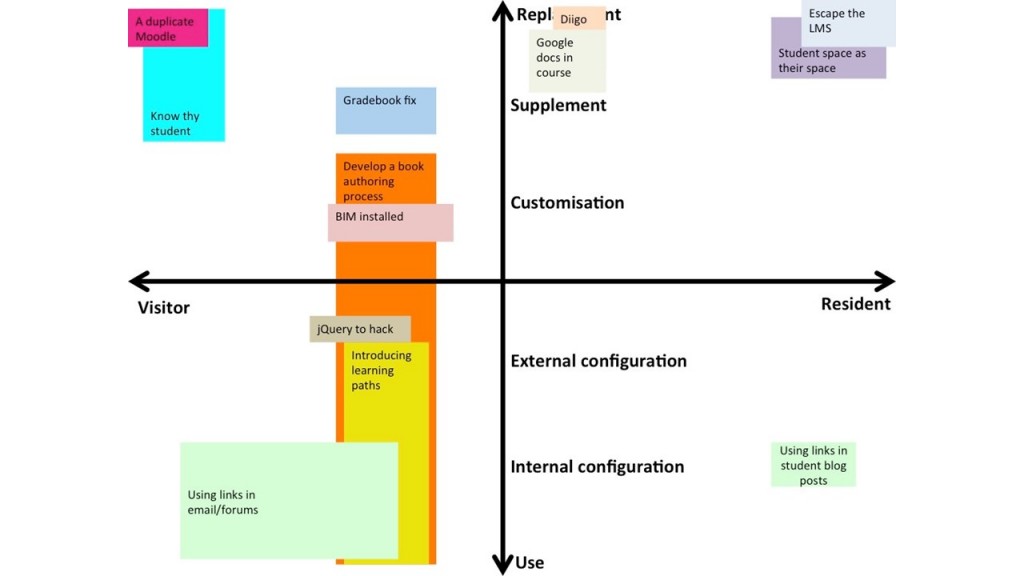

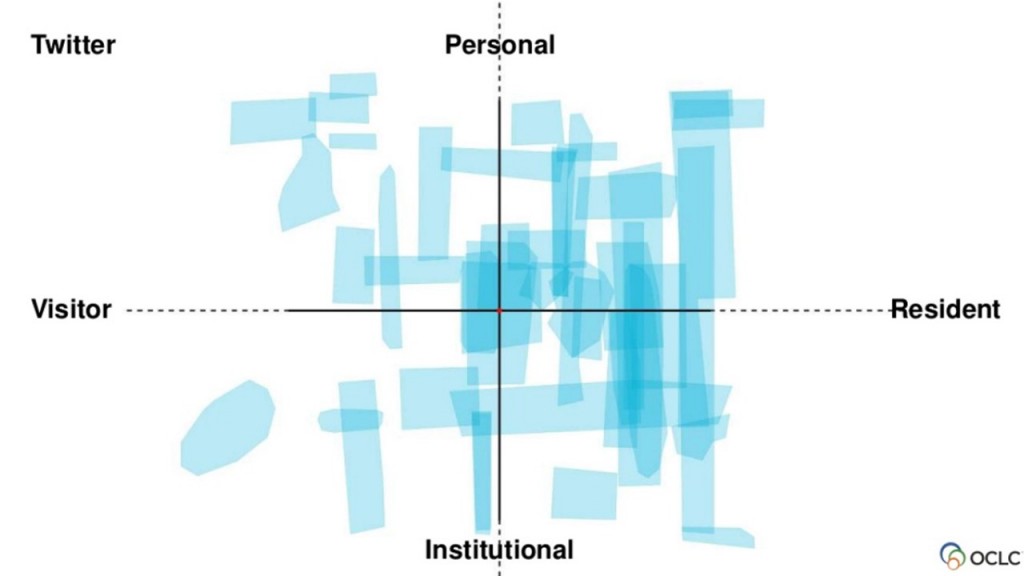

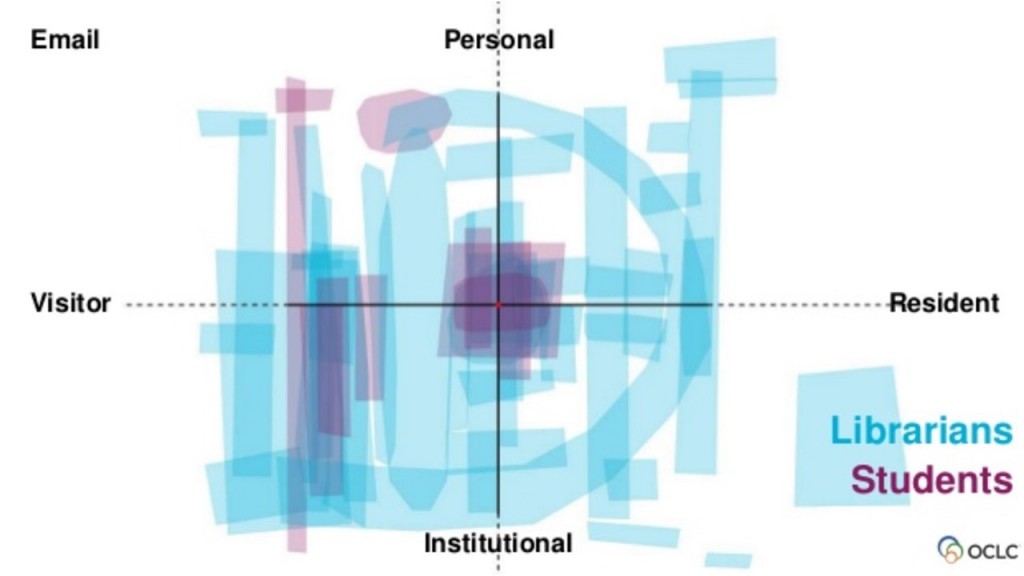

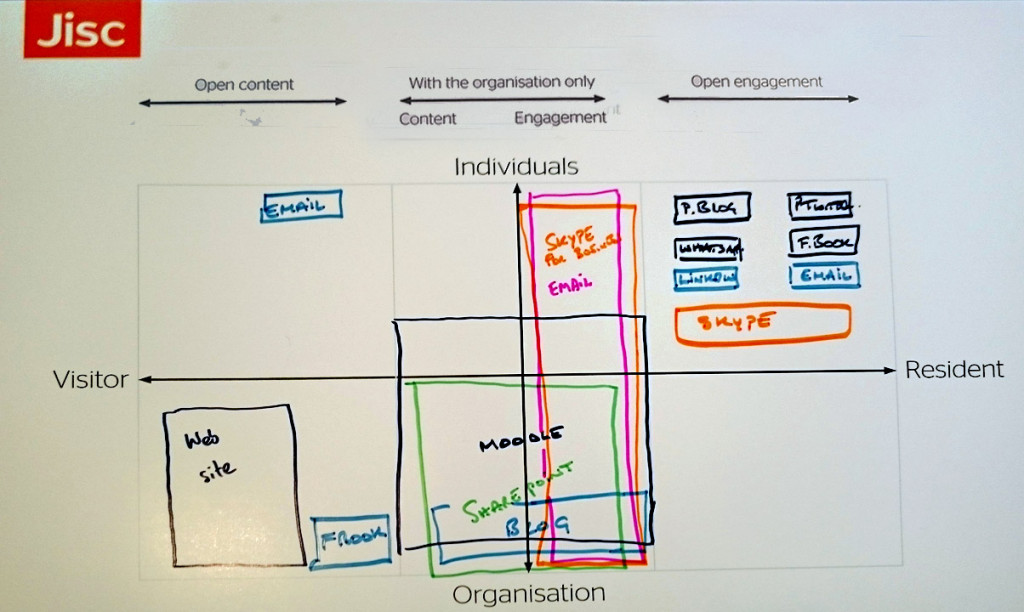

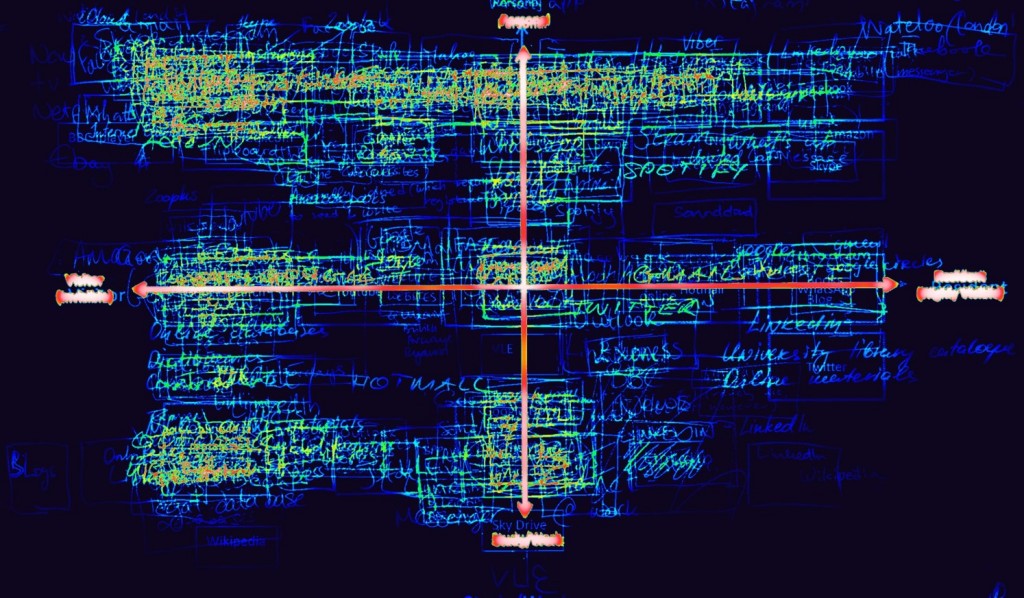

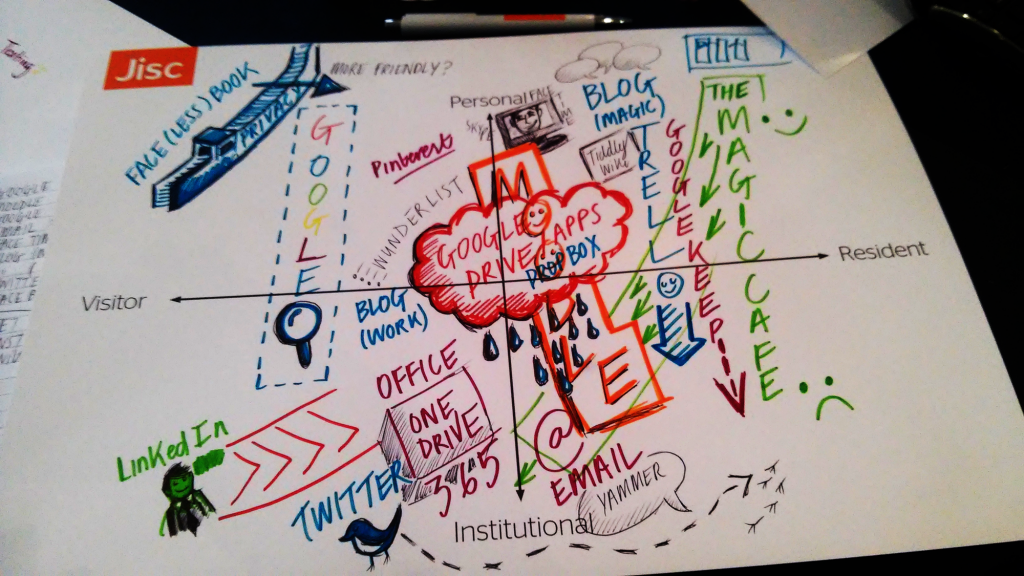

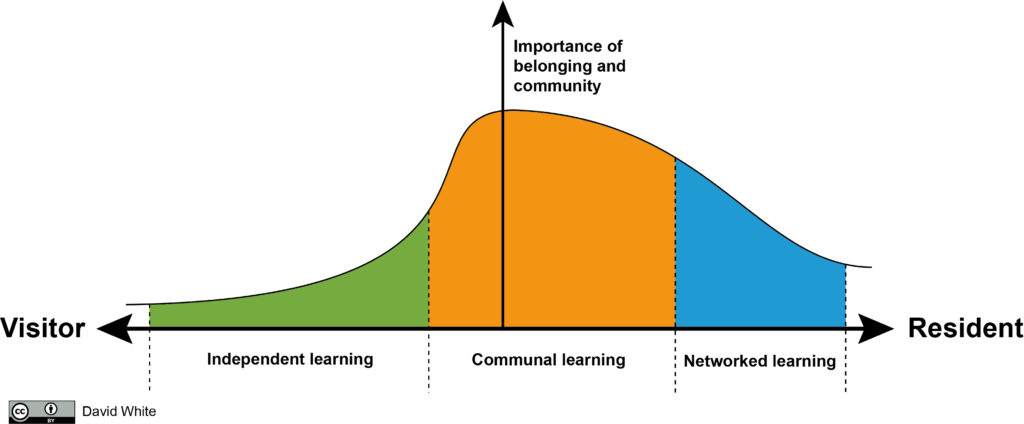

This took me back to the Visitors and Residents continuum, which is predicated on modes-of-engagement based on forms of presence. As such, it’s a simple way to map the relationship between the pedagogy (or format) of an educational offer and how this relates to the need for belonging and community.

Modes of learning (Not learning styles…)

We can trip over the language here so I’m not going to be too precious about terms, but let’s step through the diagram:

Independent learning

“Independent from what?” That’s always my question. Generally what we mean is “Learning when a member of teaching staff is not immediately present, or nearby”. This is a definition which responds to ‘contact hours’ as the underpinning principle of an educational offer and is therefore quite dangerous, especially when we consider online teaching and learning.

It’s one of the reasons that asynchronous approaches get a bad press. In terms of belonging though, we can say that those who “Just want to learn what they need” and have the ability to learn without staff input are probably not looking to ‘belong’ because they don’t have the time or the need. Here flexibility and convenience far outstrips the value of belonging. We could go a far as to say that if belonging is inconvenient then flexibility is the antithesis of belonging. (which I offer here as more of a provocation than a solid statement)

This is not to say that ‘independent’ always means ‘on your own’, which is why the belonging curve tilts up before the middle of the continuum. Self organised student study groups in various forms are a crucial part of most courses. There are no staff present, but there is a lot of learning happening and it still falls under this definition of ‘independent’.

Independent blurs into communal where the belonging is student facilitated.

In this mode we don’t need to facilitate belonging or community but we do need to acknowledge the importance of student led communities and be responsive in other ways. The danger here is that we see ‘independent’ as ‘not needing support’. This is where the concept of ‘mattering’, as discussed by Peter Felten here, is more important than the idea of belonging.

Communal learning

Key idea here is that the middle of the continuum represents engagement with ‘defined groups’. This is where we are expecting to be co-present with others and leave a social trace, but within a specific group rather than totally openly online. Members of the group will have a sense of the ‘audience’ for their contributions and some trust in shared values. They will probably also know at least some of the other members socially and/or professionally (we could look at the Dunbar Number as part of the definition here). This is why platforms such as WhatsApp suddenly became popular because they handed us back the ‘known group’ principle of privacy (on a social, not a data level) which was less exhausting than the constant maintenance of a Digital Identity or performative identity in other Social Media platforms.

The concept of a student cohort and ‘safe-spaces’ within which to learn (digital or physical) neatly fits this definition of ‘defined group’ even though being a member of a cohort is not the same as being part of a community – that depends on how the course is run.

Courses often rely on a communal pedagogy, learning together, shared endeavour (or the blunt version: ‘group work’). This is my favourtie form of teaching and learning and one of the reasons I currently work at an Art and Design focused institution. This is where belonging and community become a necessary aspect of the learning, and dare I say becoming, process of learning. It’s totally possible to support this online, but online or in-buildings, it’s expensive (time commitment, staff time, use of space, complex feedback and assessment etc) and inconvenient, especially as it usually requires some synchronous moments. Basically, you have to turn up, be present, be engaged and be prepared to compromise and negotiate. All the difficult things.

In this mode we have to design learning with presence and belonging as headline principles.

Networked learning

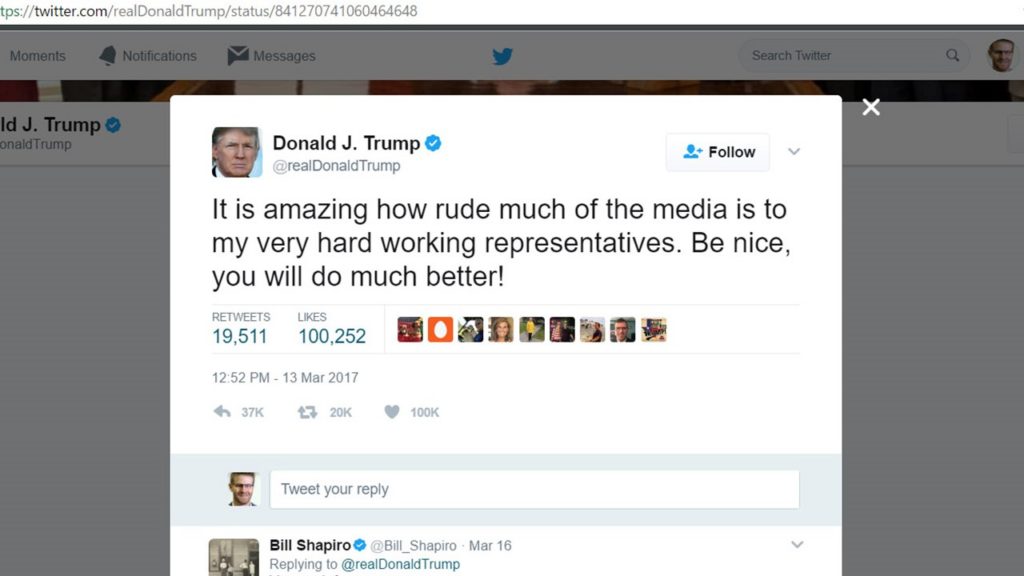

At the Residential end of the continuum activity takes place in more open and visible spaces online. These are places where anyone can see your contributions without ‘membership’ being required in a social sense (although you might need a profile on a particular platform). For example, Tweets can be read by anyone, not just the people who follow you. Instagram works in a similar way and TikTok is the ultimate hyper networked, hyper-visible, communal-through-trends-not-social-connections platform right now.

In learning terms there is perhaps less of a need for belonging and community here and more of a need to be established-within-a-network. The distinction I’m making here between communal and networked needs unpicking further but I’d suggest that a lack of clarity in this area is what has caused confusion and some anxiety in ‘open’ courses. Networked learning can fall into a performative-clique-plus-audience mode, technically ‘open’ but actually exclusive and not really a community.

Perhaps in this mode we should not be obsessed with facilitating community and more focused on being inclusive.

Multiple authentics

All of the above applies as much in residential education as it does in online. Just because students come to a building doesn’t mean that want to belong to a cohort or that they somehow automatically become part of a community. This doesn’t have to be a problem though, it’s about designing learning which is not always predicated on assumptions about our traditional, residential students (even if such a category really exists).

Sometimes at my institution we slide into thinking which implies that full, residential courses are the authentic way to learn and everything else is either geared relative to this or simply a pipeline into it. We need to design on the basis that there are multiple authentic modes of learning for multiple communities of students. Not all of these require belonging and community but where they do we need to acknowledge that it’s hard work, time consuming, and that access-to-a-building or being-in-a-cohort is not a proxy for membership-of-a-community.